The Rise of FM Radio

As the ’60s progressed, musical tastes changed and FM radio was there to welcome a new crop of rock fans.

Prologue

Of course, it was all about the music.

in the early ’60s, I listened intently to Top 40 AM stations WFIL and WIBG (“Wibbage”) playing Motown, Paul Revere & the Raiders, the Four Seasons, and Dion & the Belmonts from my family’s suburban Philadelphia home. I got a kick out of listening to Hy Lit (“Hyski O’Rooney”) on his WIBG 6-10 pm show that earned him 70 percent of the radio listening audience. Hy Lit was cool.

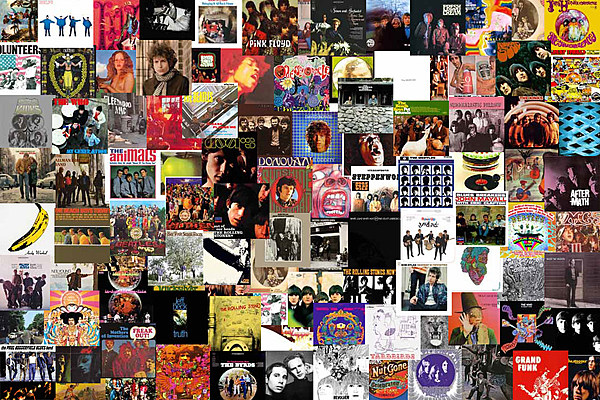

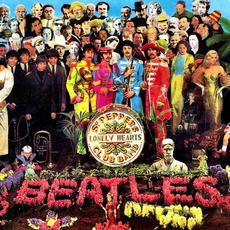

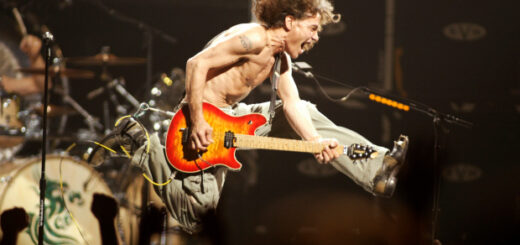

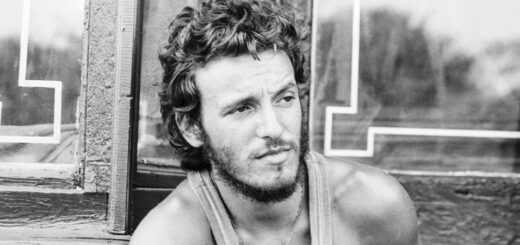

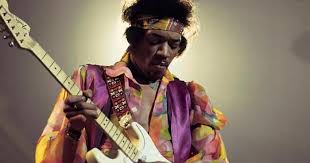

Times change. A few years later, after the Beatles schooled everyone about the infinite possibilities of the popular song, I turned my attention to the Doors, Cream, Hendrix, Dylan, the Stones, Grateful Dead, and you know the rest. There seemed to be a radio station quite willing to play these exciting new bands: WMMR 93.3 FM, the “MM” standing for Metromedia, which we thought sounded cool (it turned out to be their corporate moniker. More about them soon.)

I still listen to WMMR…on the internet, of course.

Rock ‘n’ Roll Radio

With the advent of television after World War II, radio had to reinvent itself to survive. There had to be something to attract the wide swath of listeners who made up the “baby boom.” That something turned out to be the transistor radio.

Teenagers no longer had to sit with their parents watching a grainy television screen. They could take their transistor radios beneath their bedcovers and listen to music they could call their own. A new generation of teenagers was listening to rock ‘n’ roll.

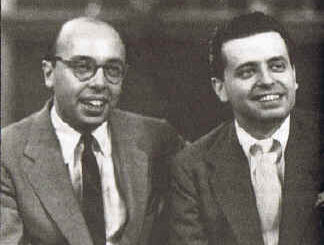

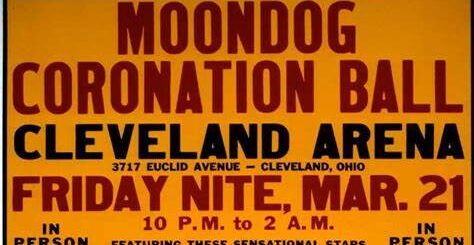

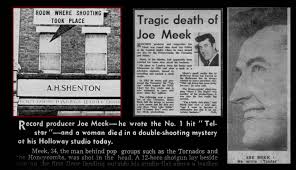

No one person was more integral to promoting new-fangled rock ‘n’ roll than Alan Freed. In 1951, Freed joined Cleveland station WJW-AM and the Moondog Show became a local, then national sensation. Freed met the moment by cultivating a hip, multi-racial, “hey, man” radio persona. Along the way, the expression, “rock ‘n’ roll” (then-Black slang for making love) spilled out of his mouth.

Freed took the fall for the payola scandal and died young. But his station’s pioneering Top 40 format, with its rigid format of “excitable DJs, contests, jingles, and a playlist of 40 hit records,” was beloved by the radio listening public.

Until it wasn’t.

Top 40 radio, as we know it today, is dead, and its rotting corpse is stinking up the airwaves.

—San Francisco DJ “Big Daddy” Tom Danohue, 1967

To repeat the lead phrase, it was all about the music.

Starting in the mid-’60s, folk rock and psychedelic rock gradually replaced their more primitive ancestors. Rock songs became more complex and sound quality was taken more seriously (headphones!). Listeners preferred buying albums of music rather than singles. FM radio, which promised a more clean, pure sound, was ready to meet the moment. FM even had a ready-made format: “Album Oriented Rock (AOR).”

But it was about the lifestyle as well. Laid-back hippiedom reigned. Fast-talking corporate striving fell out of favor. From his perch at KMPX-FM in San Francisco, Tom Donahue created an FM ecosystem that exists to this day. Elements included:

- All songs in stereo;

- Commercials kept to a minimum;

- DJs speak in a normal tone of voice;

- Songs played in their “long version” rather than the three-minute radio format;

- Songs selected from record albums, not necessarily hit singles.

In summary, it was to be the polar opposite of Top 40 radio.

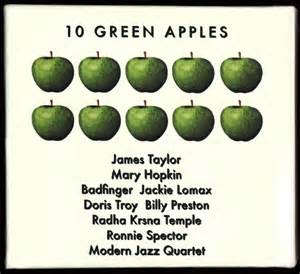

Commercial FM Takes Off

Meanwhile in New York City, the honchos at the TV and radio conglomerate Metromedia realized that Donahue was on to something. In October 1967, Metromedia changed the format of its flagship New York station WNEW-FM to progressive rock. Soon after, Metromedia lured Donahue away from KMPX to their FM station in San Francisco, KSAN, and let Donahue fine-tune, in his own words, an eclectic blend of “the best of today’s rock ‘n’ roll, folk, traditional and city blues, raga, electronic music, and some jazz and classical selections.”

By 1969, Metromedia had “reprogrammed” its affiliates in Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. It was a promising start for Metromedia, which would go on to own a record label and film studios.

Emerging FM stations, with their superior audio quality, would soon discover a natural advertising partner: record companies, which were eager to promote their progressive rock acts. FM, whose DJs officially scoffed at the commercialization of radio, would soon enjoy its three pillars of advertising dollars: record companies, stereo component makers, and concert promotion. Overall FM ad revenue spiked from $40 million in 1967 to $260 million in 1975.

“No Static At All”

A film titled FM, released in 1978, poked fun at the conflict between devil-may-care DJs and uptight corporate management. The film starred Michael Brandon, Martin Mull, and Eileen Brennan. Steely Dan wrote the film’s theme song, “FM (No Static At All).” Here is a video of the song with excellent clips from the film. published by HD Film Tributes via YouTube:

The Last DJ

Of course, the internet, satellite radio, and elaborate car entertainment systems have all diminished the dominance of FM. Rock music now competes with multiple genres. But there are many people out there, and one in particular, who embody FM’s disarming spirit of rebellion and cool. That person is Philadelphia DJ Pierre Robert (pronounced Row-BEAR).

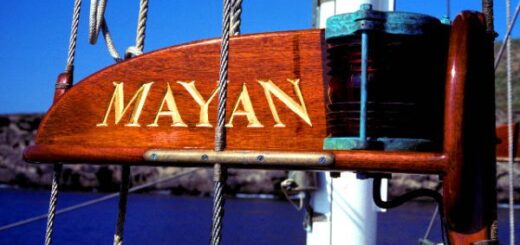

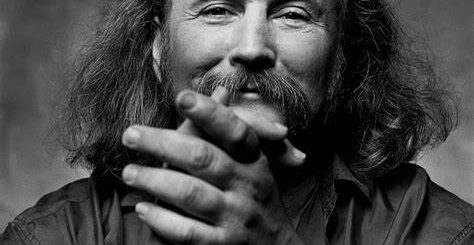

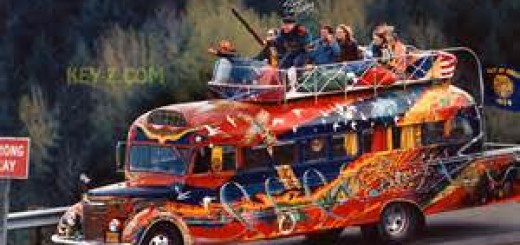

California-born Robert started his radio career at KSAN-FM San Francisco, the pioneering first FM rock station. When KSAN switched to country and western music, Robert assumed the on-air handle “Will Robertson” to protest the new format. Then, Robert loaded up his VW bus (named Minerva, pictured) and headed to Philly, where he just celebrated 43 years at WMMR.

Reflecting on his long tenure at ‘MMR, Robert told Main Line Today, “I don’t fit the mold. The city embraces anyone who’s real. I tell young DJs, ‘You have to share yourself.’ Learning to find yourself on the air takes time. How do you feel comfortable translating who you are into a microphone? I have a passion for music. I don’t care if you’re passionate about knitting; talk about it.”

Coda

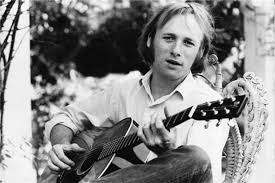

Tom Petty’s 2002 song, “The Last DJ,” laments the passing of the golden era of FM radio. Petty told Classic Rock, “I remember when radio meant something. We enjoyed the people who were on it. They were people of taste, who we trusted. And I see that vanishing.”

And there goes the last DJ

Who plays what he wants to play

And says what he wants to say

Hey, hey, hey

And there goes your freedom of choice

And there goes the last human voice

There goes the last DJ

Let’s hope not.