Stevie Wonder’s Incredible ’70s Songbook

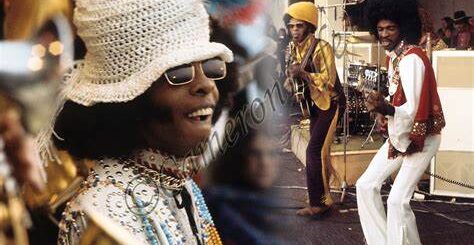

Stevie Wonder’s ‘classic period’ might be the greatest artistic streak in pop history.

Some perspective: At age 23, most folks are finishing college or military service or are at their first job, perhaps thinking of marriage and getting serious about life.

When Stevie Wonder was 23, he was amidst an incredible run of music mastery with the August 1973 release of Innervisions, an ambitious and high-minded album that catapulted him to the top of the ’70s pop music food chain.

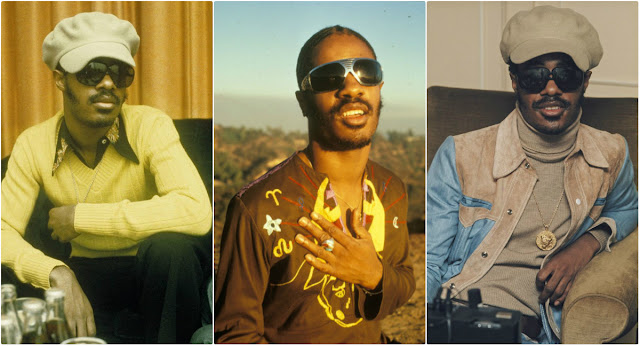

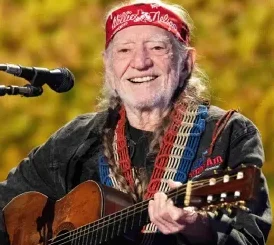

From impoverished beginnings to child prodigy to beloved pop star: Stevie Wonder has come a long way.

Motown

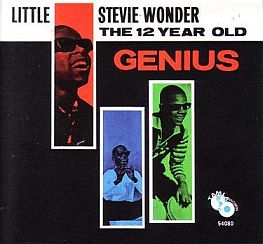

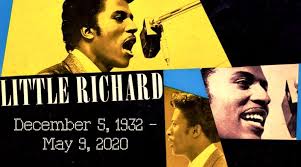

In 1961, Motown chief Berry Gordy signed Steveland Judkins, a“loose-limbed, tambourine-shaking, harmonica-blowing natural child of music,” whose voice had not yet changed. Gordy gave the 11-year-old his stage name, Little Stevie Wonder. “Genius” was a shout-out to kindred spirit Ray Charles.

Stevie Wonder learned the piano, bongo drums, and chromatic harmonica while growing up in Saginaw, Michigan. He was a born performer with an elastic voice and contagious spirit. But music careers are made in the studio, so Stevie had the best of both worlds for his first Motown single: a live recording.

The song was “Fingertips, Part 2,” (1963), Motown’s second number-one hit (the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman” was its first). Stevie Wonder is the youngest artist ever to top the charts. The song was recorded live at the Regal Theater in Chicago, with finger-snapping instrumentation and a rousing call-and-response (Clap yo’ hands a little bit louder!).

“Fingertips, Part 2”

In this video, Stevie Wonder performs “Fingertips, Part 2” on the Ed Sullivan Show, three minutes in length with robust live harmonica, published by The Jab via YouTube:

The ’60s

After “Fingertips, Part 2,” Stevie Wonder took a while to match the success of his first record. He dropped the “Little” from his stage name in 1964. He co-wrote songs for other musicians, including Smokey Robinson’s “Tears of a Clown.” As the decade progressed, Stevie remained relevant with “I Was Made to Lover Her” (1967), “For Once In My Life” (1968), and “My Cherie Amour” (1969).

Read: Unheralded Session Players Funk Brothers Key to Motown Sound

Artistic Freedom

On his 21st birthday, Stevie Wonder tapped the royalties that had accrued in a million-dollar trust fund set up by Motown Records when Stevie signed his first contract. Financially secure, he leveraged a new contract with Motown, giving Stevie full artistic control over his music.

As we shall see, Stevie Wonder used that freedom wisely.

Stevie Wonder’s ’70s Run

At the dawn of the ’70s, flush with the hard-won independence from Motown’s traditional restraints, a mature Stevie Wonder sustained a burst of creativity that would rock popular music in the ’70s. This was his “classic period” during which he recorded four critically acclaimed albums.

“The records weren’t concept albums,” wrote Rolling Stone. “but they were conceived as entities, the songs flowing together organically. The lyrics now embraced social, political, and mystical concerns.”

Musically, Stevie Wonder was in command of the studio, employing technologies such as Moog synthesizers. Stevie played most instruments, overdubbing drums, bass, and keyboards while leaving guitar solos, horns, and backup singing to others. He was no longer confined to the three-minute single or Motown’s template of romantic chest-beating.

Here are the albums:

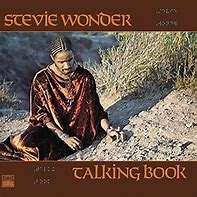

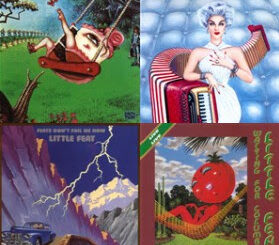

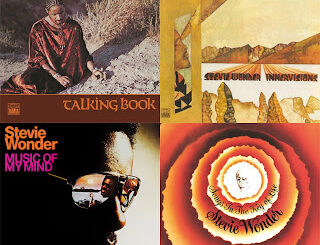

Talking Book

Stevie Wonder’s ’70s classic period had its commercial and critical breakthrough with the October 1972 release of Talking Book, which peaked at number three on the Billboard album chart. Rolling Stone trumpeted: “A work of a now quite matured genius.”

That subject on the cover of Talking Book: It sure wasn’t the manchild taking orders from Berry Gordy. The album cover featured the title and Stevie Wonder’s name embossed in braille, a sure sign of his growing independence.

Talking Book yielded two hit singles, “Superstition” and “You Are the Sunshine of My Life.” But the album’s strength rested with its unified message of empowerment and Stevie sharing the spotlight with top-notch guest talent: Ray Parker, Jr., Jeff Beck, David Sanborn, and Buzz Feiten.

Innervisions

Innervisions is considered the landmark recording of Stevie Wonder’s classic period and was honored accordingly: It won a Grammy Award for Album of the Year and a place in the Grammy Hall of Fame. It ranks number 34 in Rolling Stone‘s “500 Greatest Albums of All Time.”

The nine tracks on Innervisions are melodically satisfying and the lyrics cover some serious issues: “Living for the City,” systemic racism; “Too High,” drug abuse; Higher Ground,” reincarnation; and “He’s Misstra Know-It-All,” anti-President Nixon. “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing” emphasizes positivity and living for the moment.

Billboard declared, “In essence, this is a one-man-band situation and it works!”

Fulfillingness’ First Finale (FFF)

On August 6, 1973, three days after the release of Innervisions, Stevie Wonder almost lost his life in a car accident while en route to a radio station in Durham, North Carolina. At first comatose, his head swollen and gashed, Stevie endured months of rehabilitation. Showing scars on his forehead, Stevie Wonder was back onstage the following January. His recovery was hailed as miraculous.

Stevie Wonder revealed his spiritual side in his 1974 album FFF, a logical step considering his near-death experience.

A sampler of lyrics: “But in my heart, I can feel it, yeah, feel His spirit” and “There ain’t no room for the hopeless sinner, who will take more than he will give” and “If there is a God, we need him now.”

Compared with Innervisions, FFF is less party and more pensive. The bass lines are less funky. But the craftsmanship is there, especially in the hit, “You Haven’t Done Nothin’,” with chorus by the Jackson 5.

Paul Simon Thanks Stevie Wonder

For the second year in a row (1973-74), Stevie Wonder won the Grammy for Album of the Year with FFF. Stevie didn’t release an album in 1975. When Paul Simon won the Album of the Year Grammy for “Still Crazy After All These Years,” Simon concluded his acceptance speech with, “Most of all, I’d like to thank Stevie Wonder, who didn’t make an album this year.”

Songs in the Key of Life

It was the culmination of all that came before. He took his life experience and put them into Songs in the Key of Life.

Stevie Wonder’s 18th studio album, acclaimed as his magnum opus, was released after two years of “nonstop [recording] sessions…on both coasts, four studios…sometimes 48 hours at a time…[with Stevie] chasing his muse with a rotating crew of engineers and support musicians.” More than 130 people, including Herbie Hancock and George Benson, were involved in the epic sessions.

The hits were among Stevie’s most beloved: “I Wish,” “Isn’t She Lovely,” and “Sir Duke.” Here is a remarkable video of Stevie Wonder’s tribute to the great Duke Ellington, recorded live at the Apollo Theater in 1985, three minutes long, published by MyRhythmNSoulTV via YouTube:

Pastime Paradise

The 1976 sprawling double album included “Pastime Paradise,” one of the first songs to use synthesizers to mimic a string section. “Pastime Paradise” is dark in tone, rhythmically calling out phrases like “Race Relations” and “Exploitation” in a haunting refrain that cries out for explanation.

The song wasn’t released as a single. But it found a brand new audience in 1995 when the rapper Coolio sampled it, substituting “Gangsta’s” for “Pastime.” Coolio’s version predictably told of a bleak, crime-infested school in the inner city, where “death ain’t nothing but a heartbeat away.”

But Stevie Wonder’s original version flips the narrative in the last stanza, pleading, “Let’s start living our lives, living for the future paradise.” And isn’t that just like Stevie? He’s such an optimist. A man born Black and sightless who took his gift of song to unimaginable heights. A boy who fitted seamlessly into Motown at age 11 as if his success was preordained.

A man who created a lifetime of music in four short years in the ’70s, a feat quite possibly unsurpassed in the annals of popular music.