The Sixties Blues Revival

The blues had a baby and they named it rock ‘n’ roll.

There’s this thing we call the blues.

In its classic form, before it became just another form of popular music, the blues was an African-American man singing and playing guitar, often with harmonica accompaniment, his intense emotional expression regulated only by the music’s regimen–12 bars to a measure–and its chord structure: I, IV and V…the “flatted fifth.” That was pure “country blues.”

Among the African-American communities dotting the southern US, a blues beachhead of sorts was established in the delta region of Mississippi…Highway 61 from Vicksburg, MS to Memphis, TN. The Delta Blues, with its harsh, rhythmic style, featured performers such as Charley Patton, Son House, and especially Robert Johnson. These performers were unknown to most Americans in the first half of the twentieth century.

By the late fifties, that was about to change.

From Ballads to Boogie

In the early days of rock ‘n’ roll, many country-influenced musicians like Bill Haley stood out from the crowd by making the transition from “ballads to boogie.” Hip-swiveling Elvis Presley burst out of the Sun Studios in Memphis in 1955 with a song titled, “That’s All Right.” That song was written by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup who, 10 years prior, was the first blues performer to hit the Billboard R&B (then called “race”) charts.

Muddy Waters

As a princely practitioner of Mississippi delta blues, McKinley Morganfield chose an appropriately “delta” stage name: Muddy Waters. In May 1943 Waters boarded an Illinois Central train destined for Chicago. Muddy Waters, well-known in the bars and juke joints along Highway 61 in Mississippi, was just another migrant black southern blues musician trying to gain a foothold in the big city.

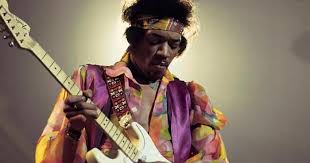

Eventually, Muddy wrote or made famous such songs as “Mannish Boy,” (Paul Butterfield, John Mayer) “I’m Ready,” (Aerosmith, George Thorogood) “Rollin’ & Tumblin'” (Cream, Bob Dylan), and “(I’m Your) Hootchie Kootchie Man” (Jimi Hendrix, Allman Brothers) that endure as rock standards.

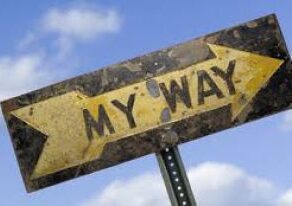

One-Way Ticket

They say the Illinois Central Railroad brought the blues to Chicago. Between 1940 and 1950, Illinois Central trains bound for Chicago mainly originated in New Orleans. Travel time to Chicago varied, of course, depending on where you boarded. Trips took up to 24 hours. In 1940 fares were $16.95 from New Orleans, $15.35 from Jackson, MS, and $11.10 from Memphis.

One way.

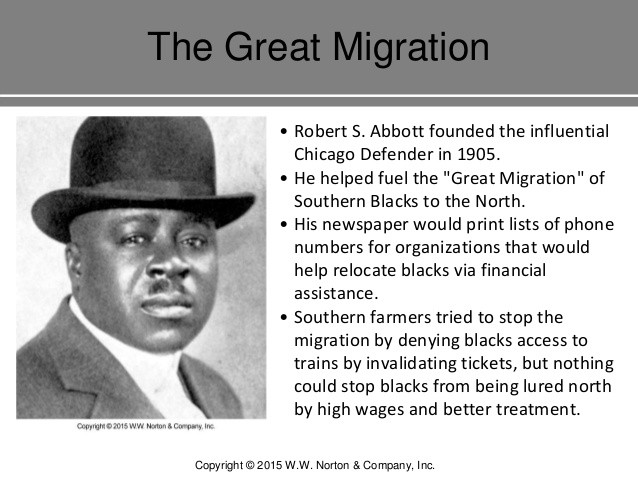

The Chicago Defender

For many southern blacks, Chicago was already somewhat familiar due to a newspaper that was widely read in black communities throughout the country. The Defender, Chicago’s black newspaper, was “actually exhorting Southern blacks to leave the farms and make Chicago their home.” It didn’t take much to convince a large number of poverty-stricken musicians to board that train. After all, Chicago was known as a “wide-open town.”

But who would listen to their music once they arrived?

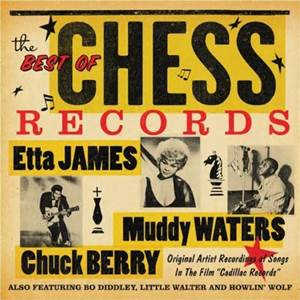

Chess Records

The brothers Chess, Leonard and Phillip, were Polish immigrants who arrived in the US on Columbus Day, 1928. They settled in Chicago and tried out their entrepreneurial talents in a variety of ways, including owning a few nightclubs. The brothers were stirred by the skill and popularity of their black nightclub performers…and astounded by the fact that no studio seemed to want to record their songs. Well, they would.

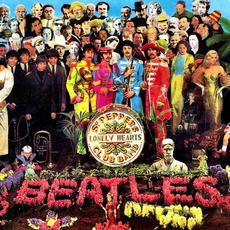

The Chess brothers bought a record company in 1947 called Aristocrat Records, and in 1950, hung their own shingle. They moved into a shiny new recording studio on Chicago’s south side, immortalized by The Rolling Stones song, “2120 South Michigan Avenue.” (Leonard’s son, Marshall Chess, went on to manage the Stones when the group broke free of London Records and signed with Atlantic in 1971.)

The Blues Crosses Over

The blues caught on with longhaired white rockers on both sides of the Atlantic in the sixties. The blues guitar, often played deliberately by Delta performers, was sped up and made crisper by blues/rock bands using new studio technology. England led the way with its lineup of blues guitar all-stars: Eric Clapton (John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers), Peter Green (Fleetwood Mac…sixties version!), Kim Simmonds (Savoy Brown), Alvin Lee (Ten Years After) and Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page of the Yardbirds.

Meanwhile in America, it seemed like many top bands were embracing the blues cadence. Texas blues guitar whiz Johnny Winter released The Progressive Blues Experiment in 1969. Canned Heat hooked up with “Boogie Chillen” Delta blues great John Lee Hooker. The J. Geils Band started out as a blues band.

The Rolling Stones started out as a blues band.

Fathers and Sons

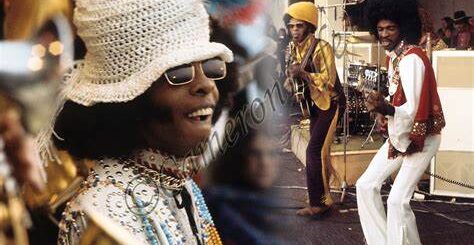

Prominent among the new American blues/rock bands in the sixties was Chicago-based Paul Butterfield Blues Band featuring Mike Bloomfield on lead guitar. On April 24, 1969, Butterfield’s band jammed with Muddy Waters at the Super Cosmic Joy Scout Jamboree in Chicago. It was a joyous occasion that clearly showed that rock and the blues had joined hands. Along with some studio work, those live performances were mixed into a groundbreaking album, Fathers and Sons.

Here is a cut from the Fathers and Sons album, published by samwise329 via YouTube. Please note that a one Jeffrey Carp is playing a rhythmic chromatic harmonica; Paul Butterfield plays the traditional diatonic blues harp.

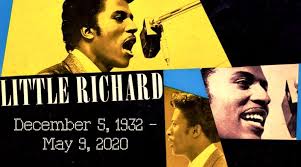

The blues renaissance in the sixties not only upheld the notion that blues music was at the core of rock ‘n’ roll. It also gave blues stalwarts such as Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Howlin’ Wolf and Little Walter a little bit of fame and fortune. It’s hard for me to think of anything more well-deserved.