Folk Music Shaped the ’60s Countercultural Revolution

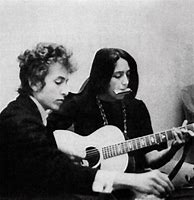

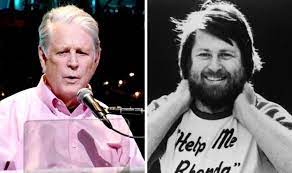

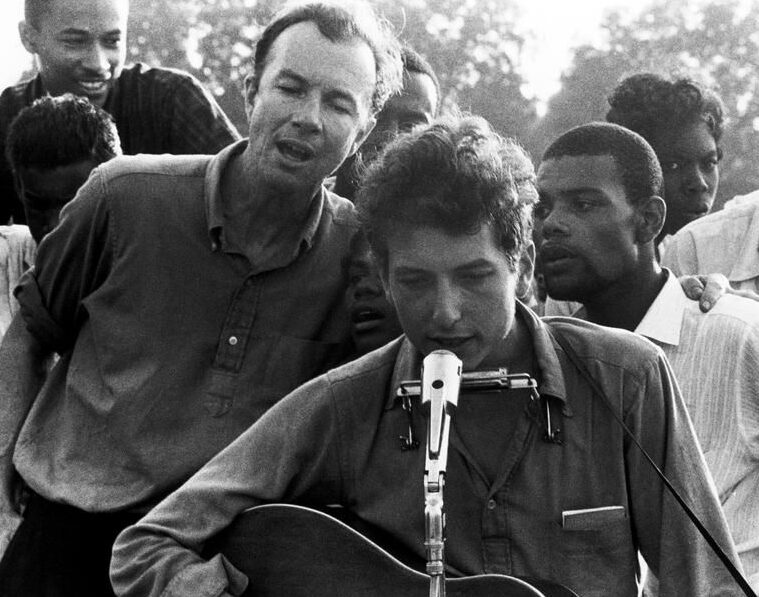

Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan down South at a 1962 voter registration rally. Seeger played a role in Dylan’s signing to Columbia Records. Photo by Danny Lyon Greenwood

Overcoming the Red Scare of the ’50s, folk music enjoyed a resurgence of goodwill in the ’60s.

High school, mid-’60s. As a dedicated rock ‘n’ roller, how could I embrace a musical genre in which the guitar is not plugged into an amplifier?

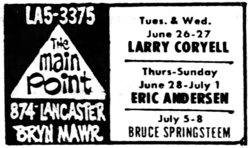

That was the question I posed to my mother when she asked me to accompany her to a coffee house in my hometown called the Main Point. It was the only club far and wide that featured folk music. I happily accepted and am grateful for it.

The Main Point

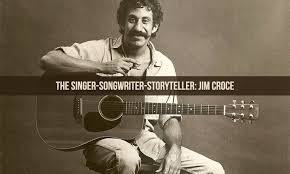

I witnessed most of folk music’s cream of the crop at this outpost on Philadelphia’s beautiful Main Line suburb. The Main Point opened its doors in 1964, right at the peak of folk music’s ascendancy. Its performance roster included: Phil Ochs, David Bromberg, Jim Croce, Tim Hardin, Odetta, Dave Van Ronk, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Tom Waits, to name just a few.

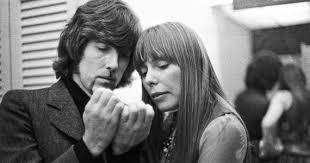

I distinctly remember my very first concert applauding Richard & Mimi Farina’s beautiful “Pack Up Your Sorrows.” I returned to the Main Point time and time again, imbued with folk music’s plainspoken oral tradition and precise instrumentation.

Folk Music: Fear and Triumph

Folk Music Revival

The folk music revival in this country became entrenched in the ’40s when there was a resurgent interest in square dancing and folk dancing. Leading performers of that period included Woody Guthrie, Josh White, Burl Ives, Theodore Bikel, Lead Belly, Paul Robeson, Ma Rainey, and Harry Belafonte.

Here is the great Theodore Bikel in a 1963 duet with Judy Collins singing “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine,” (adapted by Jimmie Rodgers) on the TV show Hootenanny, published by Historic Films Stock Footage Archive via YouTube:

Woody Guthrie

Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) was critical to the success of folk music. Born dirt poor in a small town in Oklahoma, Guthrie moved to New York City in 1940 and wrote his most famous song, “This Land Is Your Land,” said to be an answer to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” During that year, Guthrie played a benefit for California farm workers. This is where he met Pete Seeger and the two became good friends.

But Woody Guthrie would be absent for many of folk music’s triumphs. By the late ’40s, his mind and body were ravaged by Huntington’s Disease. His 1961 summit with Boby Dylan occurred in a New Jersey hospital.

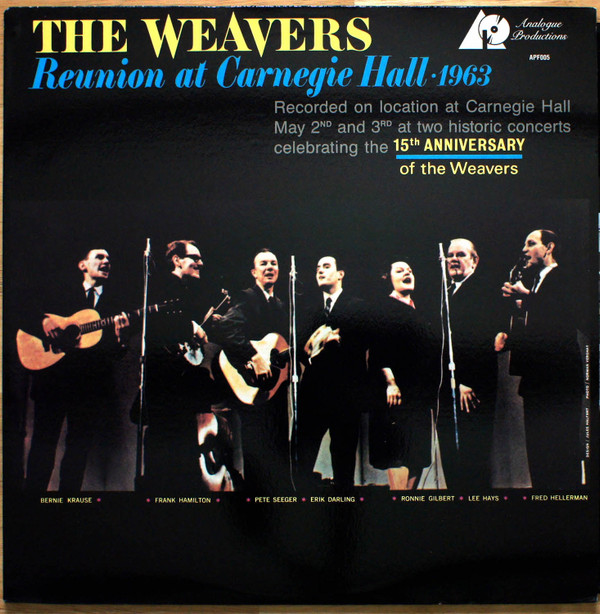

The Weavers

In 1948, the Weavers formed in New York City. Pete Seeger’s band landed a number-one hit on the Billboard charts in 1950 with the Lead Belly penned, “Goodnight Irene.” It was the first commercial hit of the folk revival.

During the ’40s and especially the ’50s, folk music was associated with acoustical guitars (ha, until Bob Dylan’s appearance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival) and political dissent. Perhaps reacting to post-war conformity, unconventional musicians on the coffee house circuit carried the message of the labor movement (Pete Seeger, Utah Phillips), civil rights (Joan Baez, Odetta), and peace (Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton).

The Red Scare

There was little doubt where the biggest names in folk music stood politically. Some would pay dearly for it.

This was the era of Sen. Joe McCarthy, the House Un-American Activity Committee (HUAC), and the Hollywood Ten. Accused of being members of the Communist Party, Seeger and fellow Weaver Lee Hayes were called on to testify before HUAC in 1955. Both men refused to testify on First Amendment grounds and Seeger was found guilty of contempt.

The Weavers were placed under FBI surveillance and were forbidden to perform on radio or TV. Decca Records canceled the band’s recording contract. Blacklisted, the Weavers disbanded.

Triumphant Return

The Weavers’ inactivity didn’t last long. The group reunited to play a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall. The band released a live album in 1957, The Weavers on Tour. By the late ’50s, folk music’s popularity was surging and McCarthyism was fading.

Seeger’s conviction was overturned on technical grounds in 1961. He spent the ’60s active in the civil rights movement and writing anti-war songs such as “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and the biblical “Turn! Turn! Turn!” (covered by folk-rockers, the Byrds).

The ’60s Folk Music Revival

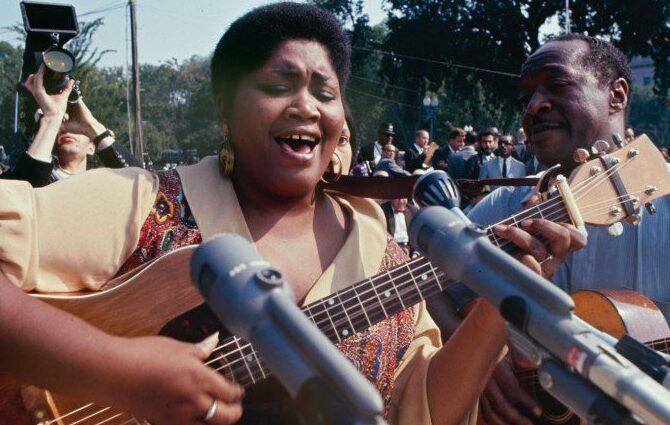

Folk music took off in the ’60s, energized by the civil rights movement and campus protests against the Vietnam War. In a moment of cultural import, folk music luminaries gathered at the dais of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s historic speech during the 1963 March on Washington. Joan Baez led Bob Dylan, Josh White, Theodore Bikel, and a crowd of 3,000 to sing, “We Shall Overcome.”

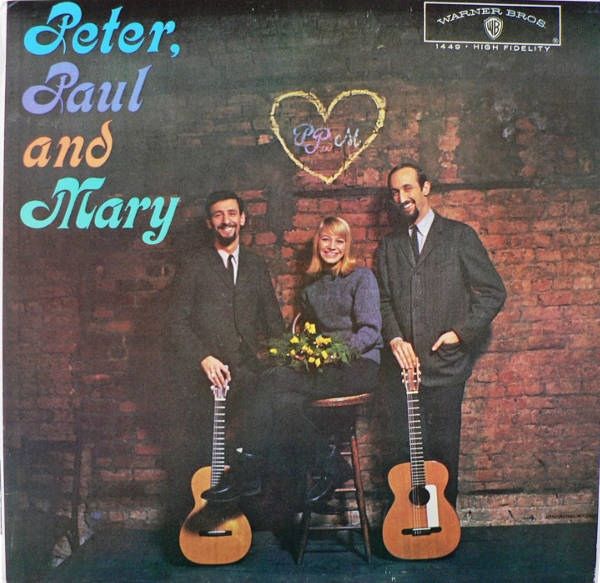

MLK introduced Odetta as “the queen of folk music.” Notably, Peter, Paul and Mary performed Bob Dylan’s implicit anti-war song, “Blowing in the Wind.” Peace and civil rights. These were the recurring themes in folk music’s ’60s renaissance.

’60s Folk Songs

Here are ten folk songs, in no particular order, that helped shape the ’60s countercultural revolution:

Bob Dylan – The Times They Are A-Changin’

Pete Seeger – Which Side Are You On

Joan Baez – Joe Hill

Phil Ochs – I Ain’t Marching Anymore

Kingston Trio – Where Have All the Flowers Gone?

Peter, Paul and Mary – If I Had a Hammer

Odetta – Oh, Freedom

Richard & Mimi Farina – Birmingham Sunday

Buffy Sainte-Marie – Now That the Buffalo’s Gone

Woody Guthrie – Tear the Fascists Down

’60s protests fragmented toward the end of the decade, as drugs, opportunists, and political adventurism took their toll. But folk musicians were, for the most part, unshaken and steadfast. Amid calls to turn on, tune in, and drop out, they were the adults in the room.