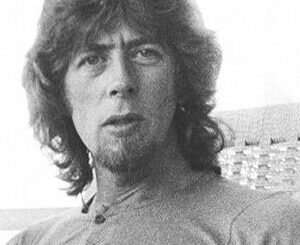

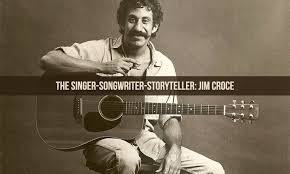

Paul Butterfield Was My First Blues Harmonica Hero

Butterfield’s swagger and his command of the blues harp created a link to white rock audiences.

Prologue

During my freshman year at Penn State, filmmaking might have been my major but rock music consumed my life. The year was 1969 and I don’t need to recount the abundance of bands beckoning us to get ourselves back to the garden and set our souls free. We lived it, breathed it and reveled in it.

One typical Friday night, as we were playing air guitar to the Allman Brothers, I made a pact with a friend I’ll call John: Let’s start a rock band and see how far it goes. But we would need to learn instruments first. John chose the bass guitar.

I chose the blues harmonica. Reasons: I loved the blues, first and foremost. And, ha! my load on gigs could be carried in my pocket.

We eventually started a band and my blues harp did gain a following on campus. But then life happened and we scattered. I left campus with four or five Hohner Marine Band harps and a reverence for the “hard puffing, hard-living” king of the blues harmonica, Paul Butterfield. I wanted to be just like him.

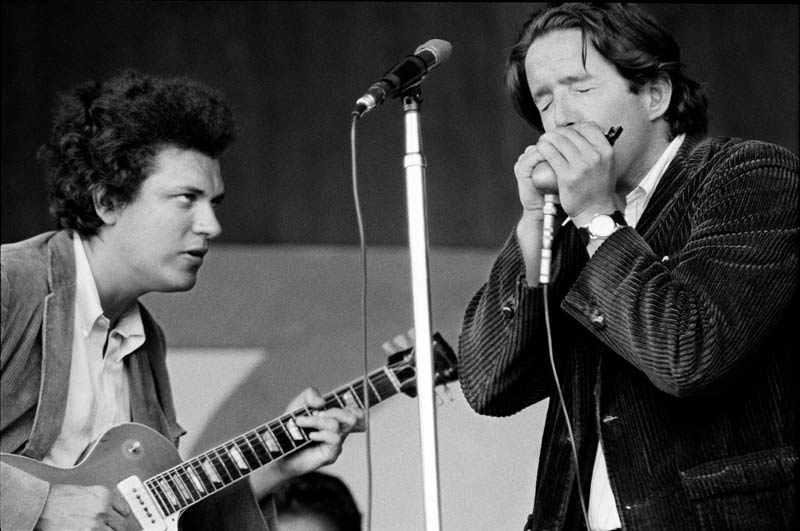

A proper introduction is in order. This video, just a minute and a half short, shows Butterfield and his original blues band playing a shuffle at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, a pivotal moment in Butterfield’s career (more about this soon), with guitarist Mike Bloomfield providing a vocal introduction, published by Mark Marcade via YouTube:

“Born in Chicago”

Paul Butterfield was born in Chicago, not in 1941 as his first album’s lead song, “Born in Chicago” suggests, but in 1942. The actual writer of that song, guitarist Nick Gravenites, was born in 1938, and now I’m all confused. (It was probably a rhyming device.)

The son of a painter and a lawyer who settled in Chicago’s tony Hyde Park neighborhood, Butterfield spent his early years studying classical flute and pursuing a track & field scholarship. An injury sent young Paul spinning in a radically different direction.

Blues Adventures on the South Side

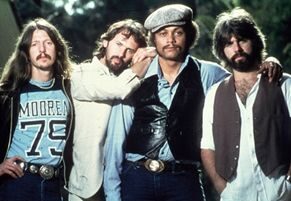

With best buds Nick Gravenities and Elvin Bishop in tow, Paul Butterfield in the late fifties started hanging out on Chicago’s South Side, as far from Hyde Park as the mind could imagine. The young men loved blues music and here they were, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Rush, Little Walter and the great Muddy Waters. It must have been a heady time for three white boys from the ‘burbs.

Elvin Bishop recalls: “By the time Butter had been hanging out the ghetto for a couple of years, he was part of the scene and getting accepted.”

“Butter”

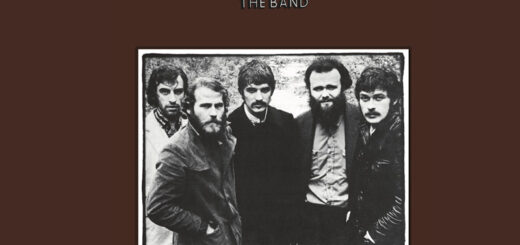

Paul Butterfield achieved a sound on the blues harp that was known for the purity and intensity of its tone. The Band drummer Levon Helm was a big fan: “What a touch he had! He could hit a single note and make it sound like a full orchestra.”

His attachment to the blues harp gave him the solitude he apparently craved. His brother Peter remembers:

He…spent an awful lot of time, by himself, playing [harmonica]. He’d play outdoors. I can remember him out there for hours, playing…It was a very solitary effort. It was all internal, like he had a particular sound he wanted to get, and he just worked to get it.

Peter Butterfield

There are some friends and associates who described Butterfield in not-so-flattering terms. Producer Norman Dayron: “Very quiet and defensive and hard-edged.” Writer and AllMusic founder Michael Erlewine: “always intense, somewhat remote and, on occasion, not too friendly.” Mike Bloomfield (before they became good friends): “He was down there on the South Side, holding his own… I was scared to death of that cat.”

But band co-founder and guitarist Elvin Bishop saw the positive side of Butter’s hard edge. “Paul had a very strong way about him,” recalled Bishop. “He gave us high standards to reach for and operate under. And when he got in front of a crowd, he wouldn’t take no for an answer. He’d keep getting more and more intense until he got them going.”

Â

1965

First Album

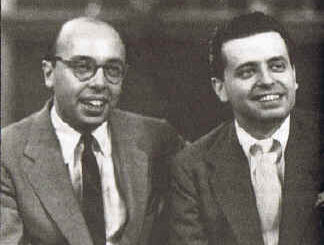

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s self-titled first album was deemed by critics, “Chicago electric blues with a rock urgency.” In late 1964, Elektra Records house producer Paul A. Rothchild was told that “the best blues band in the world” was playing at Chicago clubs. Rothchild flew to Chicago and caught Butterfield’s act. He then saw guitar prodigy Mike Bloomfield with a different band.

Bloomfield was a busy man in 1965, helping Bob Dylan record what sounded like a keeper, “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan admired Bloomfield’s “fluid, clean, chiming guitar sound.”

The pairing of Butterfield and Bloomfield seemed to put the band on another level. Elvin Bishop would have to be satisfied with rhythm guitar. The rhythm section–Jerome Arnold on bass, Sam Lay on drums–was recruited from Howlin’ Wolf’s touring band. Keyboardist Mark Naftalin made the band a sextet.

The album was released in October 1965. No singles were released but songs such as “Blues with a Feeling,” “Mystery Train,” ” Got My Mojo Workin’,” “Look Over Yonders Wall,” and “Mellow Down Easy” endure.

The 1965 Newport Folk Festival

July 25, 1965. Two men arrived in Newport, Rhode Island, both determined to create a stir among the folkies gathered for the festival. One of them was Paul Butterfield, hardly a household name outside his Chicago home base. Butterfield was recently signed to Elektra Records but had yet to release an album.

Butterfield didn’t disappoint. It can be said without a doubt that the Paul Butterfield Blues Band served up authentic electric Chicago blues to a grateful and enthusiastic folk audience. Here’s a video of the band playing “Born in Chicago” at Newport, just short of two minutes, with Mike Bloomfield again verbalizing, published by BestMasterGuitar via YouTube:

Dylan’s Electric Gambit

Oh, yes, that other fellow who happened upon Newport on that summer weekend in 1965 was of course Bob Dylan. Dylan just released a song, “Like a Rolling Stone,” just five days prior (Jul. 20), with a sound that was a far cry from the acoustical gems for which he was revered. Dylan was adamant about sharing his new electric sound with a crowd who regarded Bob as one of their own. He just needed musicians with electric instruments to make it happen. Butterfield’s band was his first and only choice.

So, to a chorus of boos from an audience of folk music “purists,” Bob Dylan took the stage with Butterfield’s rhythm section of Jerome Arnold and Sam Lay, Barry Goldberg on keyboards and two of the musicians who helped Dylan make “Like a Rolling Stone” a masterpiece, Al Kooper and Butterfield lead guitarist Mike Bloomfield.

Testimony

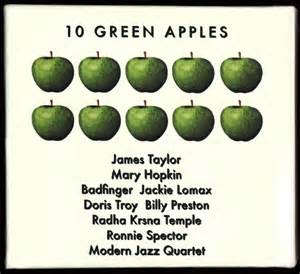

With Newport and the release of his first album, the musical gods smiled brightly on Paul Butterfield in 1965. It was as if they had chosen Butterfield to introduce black blues to a white American mass market. “I knew it was our historic movement,” remarked keyboardist Mark Naftalin. “It was in our generation that the reverence for blues artists and their music swept into the white world.”

“I don’t know how many people have told me over the past 50 years that it was the Butterfield Blues Band that got them into music,” remembered Elvin Bishop. “We were at the right place at the right time because there was this huge, beautiful body of music–the blues–and a huge white American audience. And the two never really got together.”

Snippets from a Life

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band followed up its first album with one titled East-West the next year, in 1966. The title implied an “Indian raga” musical component, a sort of “modal jazz” favored by Miles Davis. Mike Bloomfield played a sterling elongated solo on the title track. My favorite song, “Work Song,” featured Paul Butterfield’s “hard bop” harmonica at its melodic best. East-West tried very hard not to be a blues album.

In April 1969, a concert was held in Chicago that paired three from Butterfield’s old band (Butterfield, Bloomfield and Sam lay) with blues luminaries such as Otis Spann, James Cotton, Buddy Miles and Muddy Waters. The Super Cosmic Joy Scout Jamboree was just one more reminder that blues had become multi-racial (and aimed to stay that way).Â

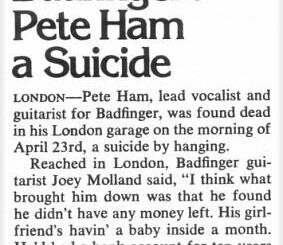

Decline

I met Paul Butterfield during the mid-eighties when he played a blues club in Dayton, Ohio. Since I knew the club’s owner, I was there with Butterfield at the owner’s table between sets. He freely admitted to not doing that well; he checked off a heroin habit, freebasing cocaine and drinking lots of tequila as the main culprits to his health. He looked terrible. But onstage, he could still capture that magic and the audience loved him.

Butterfield died in 1987 at age 44 of a heroin overdose. His old friend Mike Bloomfield died in 1981 of an apparent drug overdose.

Legacy

But before we mourn a life that could have been much more, let’s admire one particular achievement that only Paul Butterfield can claim. I’m not referring to gold records or Grammy awards.

Butterfield is the only artist to have played at all of the consequential concerts that defined the rock era: Newport, 1965. Monterey, 1967. Woodstock, 1969. The Last Waltz, 1976.

Paul Butterfield made it count.