“John Barleycorn Must Die!” the Best Drinking Song Ever?

The story behind Traffic’s deep dive into British folk music.

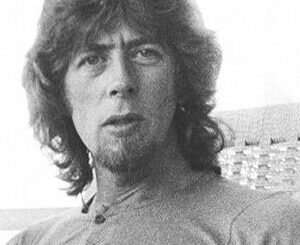

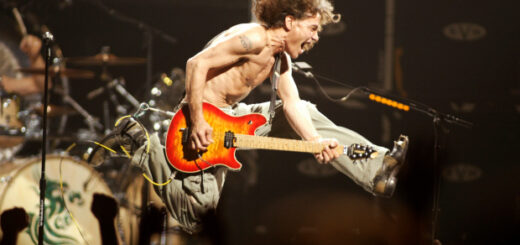

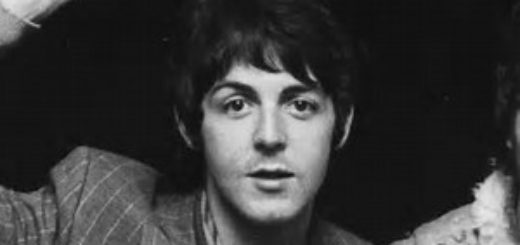

Prologue: Steve Winwood

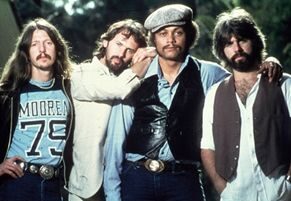

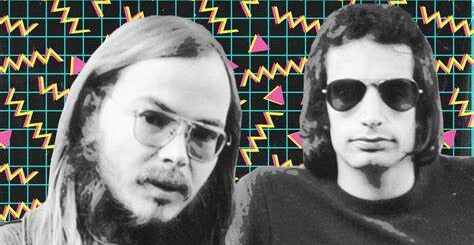

At the center of it all was “boy wonder” Steve Winwood, perhaps our generation’s most prodigiously gifted rock artists. Along with talented guitarist-songwriter Dave Mason and others (we’ll get to them), Winwood formed the rock band Traffic in the late sixties and delighted us with two supremely sublime record albums right off the bat.

The first, Mr. Fantasy, released in 1967, was a bit lacking in song content but hooked us with a pleasing psychedelic ambience. Then there was the self-titled Traffic (1968), certainly a sixties masterpiece. Every song seemed flawless and memorable, with Dave Mason playing an outsized role in contributing “Feelin’ Alright?” “You Can All Join In,” “Vagabond Virgin” and “Cryin’ To Be Heard.” Winwood showed major songwriting chops with the song, “Forty Thousand Headmen.”

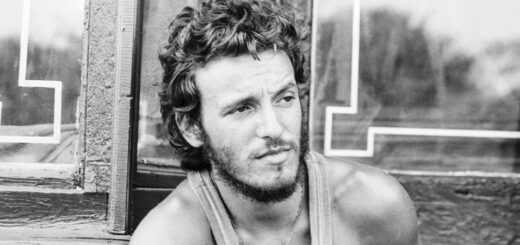

Blind Faith

But Dave Mason was halfway out the door by the end of the Traffic sessions, the second time he walked out on the band. Steve Winwood joined Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker to form the supergroup Blind Faith. The band recorded one excellent album and called it quits. Winwood followed drummer Baker for a brief moment in Ginger Baker’s Air Force.

At the beginning of 1970, Steve Winwood returned to his studio ostensibly to make a solo album, with the working title of Mad Shadows. The idea was for Winwood to play all the instruments himself, as Paul McCartney did in his first solo effort. But that didn’t last long. Winwood realized it was a “weird” way of making music.

“the whole thing that makes music special is people,” Winwood was quoted in The Music Afficianado. “It seemed inhuman to make records just by overdubbing.”

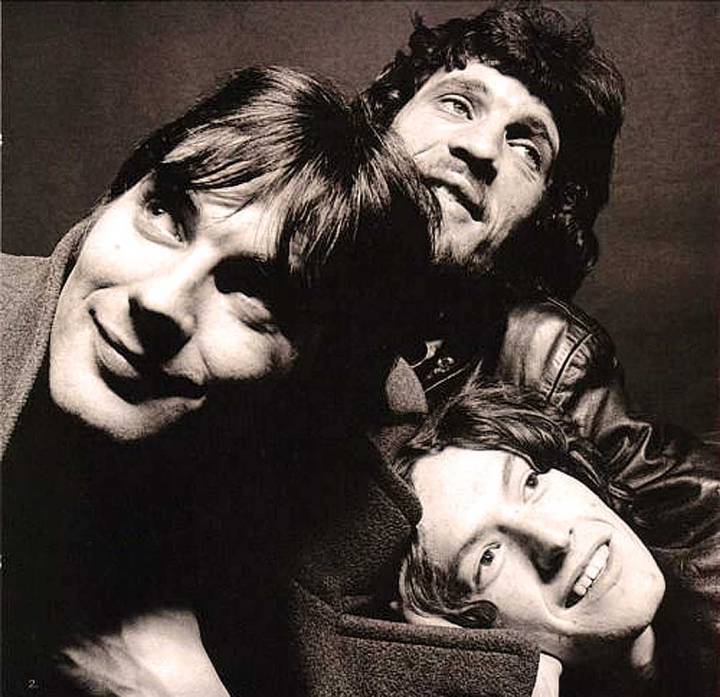

So Winwood called on some old friends from his Traffic days. Drummer and vocalist Jim Capaldi, Winwood’s songwriting partner, said yes to his mate. Flutist and reedman Chris Wood joined them in the studio soon after. Traffic was reborn.

The Barleycorn Sessions

Chris Wood had eclectic tastes in music and was more than happy to share them with the band. Wood was especially influenced by the folk music revival that was catching on in both England and America in the mid-sixties. The British folk scene was vibrantly led by the likes of Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span and Fotheringay.

One song that caught Chris Wood’s ear was “John Barleycorn” by the Watersons on its 1965 album Frost and Fire. This particular version was a vocal performance with no musical accompaniment.

Traffic’s recording had Steve Winwood on guitar, Jim Capaldi on sparse percussion and vocal harmony beginning with the fifth verse and of course Chris Wood’s indispensable flute.

Here, then, is a version of “John Barleycorn Must Die,” with Steve Winwood all by himself on acoustic guitar in 2012, published by Steve Winwood via YouTube. Listen to the words!

The Album

As it turned out, John Barleycorn was the only folk-type song on the album. The five other songs were pure rock ‘n’ roll, with the exception of the opening number, “Glad,” This song was a rousing, jazz-influenced instrumental, a seven-minute barn-burner that received heavy radio play despite its length.

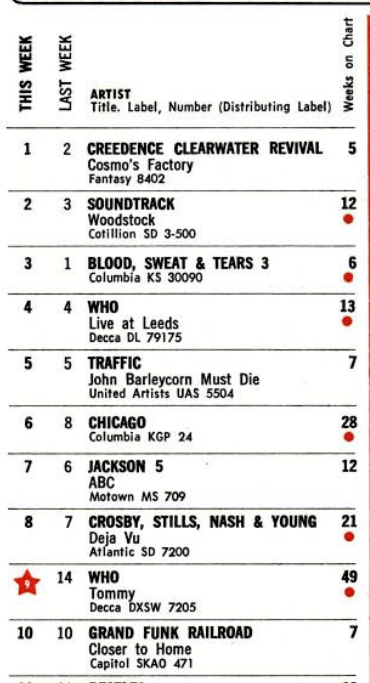

John Barleycorn Must Die was Traffic’s highest-charting album in the US, going to #5 on the Billboard 200 (see below).

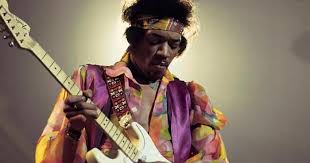

The Meaning of John Barleycorn

In British folklore, John Barleycorn is the fictional, sometimes humorous personification of alcohol. The character could represent the crop of barley harvested each summer that both symbolizes the wonderful drinks that are made from barley (beer and whiskey) but endures the indignities and hardships that come with the cyclical nature of planting, growing, harvesting and then death.

References first appeared around 1620. The renowned Scottish poet Robert Burns reworked a trove of folk material for his epic poem “John Barleycorn” (1787).

A Great Drinking Song?

Here is the last verse of “John Barleycorn Must Die” from Traffic’s version:

And little Sir John and the nut brown bowl and his brandy in his glass,

Steve Winwood, Traffic

And little Sir John and the nut brown bowl proved the strongest man at last,

The huntsman he can’t hunt the fox nor so loudly blow his horn,

And the tinker he can’t mend kettle or pots without a little barleycorn.

After the song’s first listen, you ponder the brutality inflicted by three men on a tragic figure named John Barleycorn. Or could these distressing lyrics be a metaphor for the difficult process of harvesting barley in order to make an alcoholic beverage? A fine glass of whiskey or beer to get us through the toughest of days?

Works for me.