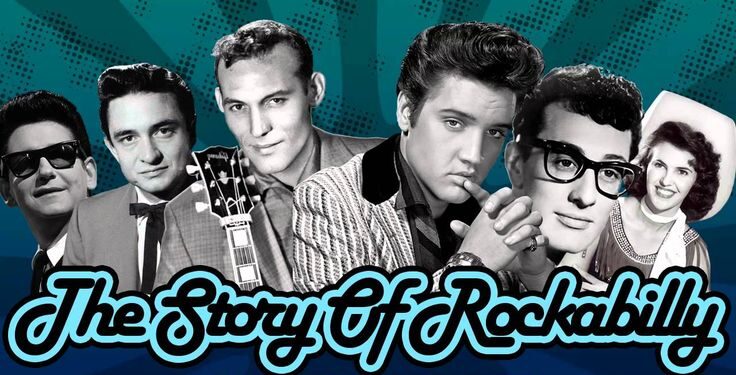

Rockabilly: Short Shelf Life, Long on Memories

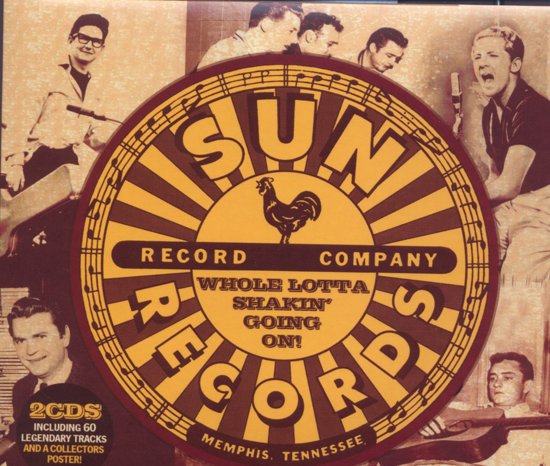

Sun Records was ground zero for rockabilly, which literally means rock ‘n’ roll performed by hillbillies.

15 Minutes of Fame

For a musical genre that lasted for, oh, about a decade, rockabilly’s impact on popular music is outsized and enduring. Rockabilly’s spirited fusion of country and Black rhythm & blues set in motion rock ‘n’ roll’s appropriation of American youth culture.

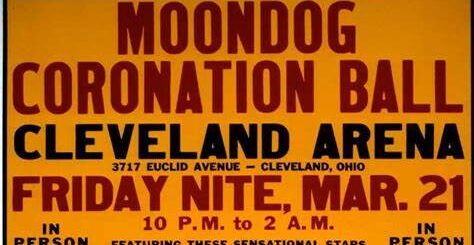

Rockabilly was here and gone in a flash. It began in 1954, according to Rolling Stone, with Elvis Presley’s first recording for Sun Records (Sun No. 209), “That’s All Right (Mama),” written by Delta blues singer/guitarist Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. (More about this soon.) The next year, Carl Perkins wrote and recorded what many consider to be rockabilly’s anthem, “Blue Suede Shoes.”

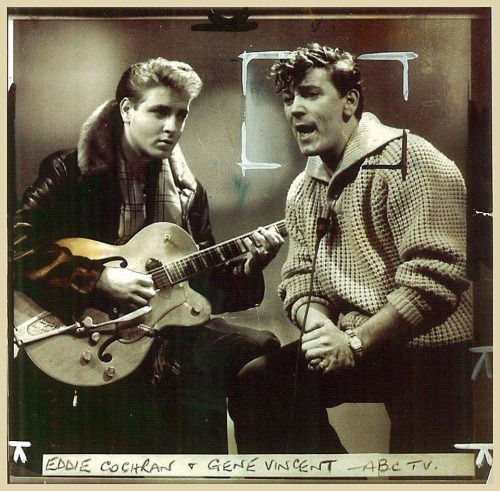

Rockabilly’s diminishment as a distinct genre was brought about by a chain of unfortunate events to its key players: Carl Perkin’s 1956 car accident and lengthy convalescence; Elvis’s induction into the military in 1958; and the 1960 London taxi accident that killed Eddie Cochran and injured Gene Vincent during a concert tour of England.

Read: How Rock ‘n’ Roll Began

The disclosure that Jerry Lee Lewis married his 14-year-old cousin Myra didn’t help matters.

Sun Records

If I could find a White man who had the Negro sound with the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars. That’s what I heard in Elvis, the Negro sound.

–Sam Phillips

Well, Sam Phillips fell a bit shy of his billion (he sold Elvis’s contract to RCA for $40,000, worth $460,000 today). But his impact on popular music and his formative influence on rock ‘n’ roll are indisputable. A former DJ and radio engineer, Phillips founded Sun Records in 1952 in Memphis, Tennessee, with a storefront sign that read:

We Record Anything – Anywhere – Anytime!

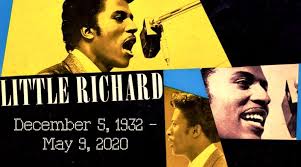

Memphis is the northern point of the famous Mississippi-based “Blues Highway 61,” the home and base of hundreds of working blues musicians. Phillips used this pipeline to record Black blues musicians. Three notables: the great Howlin’ Wolf; Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats whose song, “Rocket 88,” is called by some the first rock ‘n’ roll record; and Junior Parker, whose “Mystery Train” was covered by Elvis in 1955.

Southern Men

Sam Phillips’ R&B and blues recordings began getting radio play, and that lured young White musicians to Sun Records. Â A Sun producer, “Cowboy” Jack Clement, discovered and produced Jerry Lee Lewis in 1956. The Killer’s defining hit, “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” was first recorded in 1955 by Big Maybelle.

Tennessee sharecroppers’ son Carl Perkins drove to Memphis to audition for Phillips after hearing Elvis’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky” on the radio. Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes” made him the first White country artist to cross over to the R&B charts.

The great Johnny Cash moved to Memphis in 1954Â and got a job selling appliances. While singing at nightclubs, someone suggested he visit Sun Records. Cash sang mostly gospel music during his audition with Phillips, who suggested Cash find more lively songs that could become hit records. Johnny Cash’s first recordings at Sun, “Hey Porter” and “Cry Cry Cry,” were modest hits on the country charts in 1955.

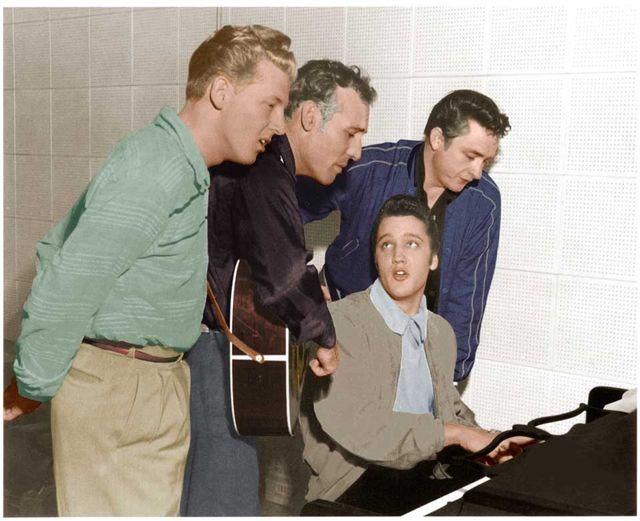

“The Million Dollar Quarter”

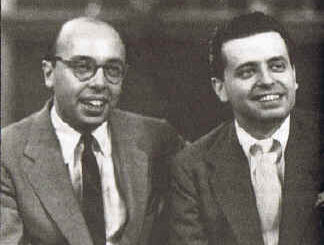

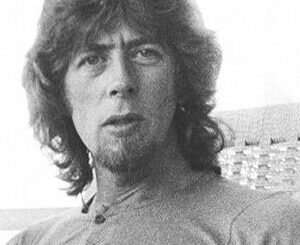

The Million Dollar Quartet: Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, and Johnny Cash, on December 4, 1956, at Sun Records. Source: Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images

The Essence of Rockabilly

Rockabilly and rock ‘n’ roll share the same musical synthesis: Black rhythm & blues and White country music. The difference between the two lies in rockabilly’s roots in the South, where supposedly hillbillies live. Accordingly, rockabilly is a subgenre of rock ‘n’ roll.

Distinct characteristics of rockabilly include:

- Rockabilly songs were written in the 12-bar blues chord progression and performed in a fast, upbeat, high-energy tempo; ballads were few and far between.

- Rockabilly singers favored “deep, over-heated” vocals enhanced by echo and reverb. Vocal “hiccups” were wielded by Buddy Holly, Gene Vincent, and others. Guitars were twangy. Upright bass players thumped a “slap-back echo” that kept time flamboyantly.

- Echoing early rock ‘n’ roll, rockabilly songs were two to three minutes in length.

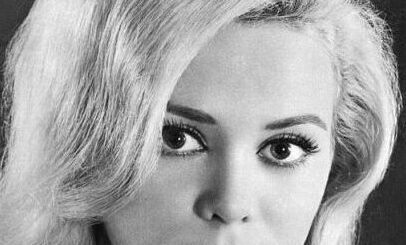

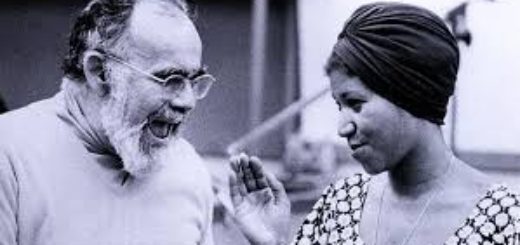

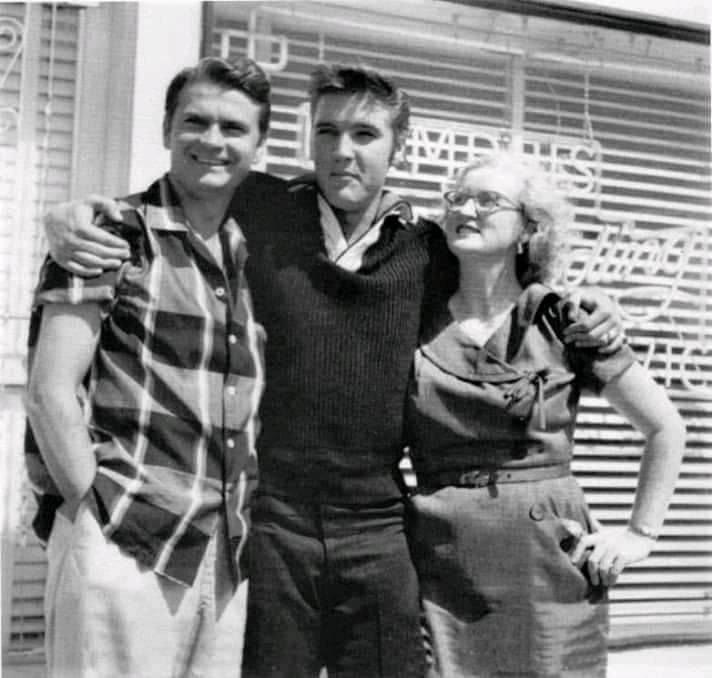

Memphis, Sep. 23, 1956. Sam Phillips, the King, and Sun Records producer Marion Keisker. Source: Michael Ochs/Getty Images

70 Years Ago Today

It was 70 years ago, on July 5, 1954, Sam Phillips recorded “That’s All Right (Mama)” by an unknown truck driver named Elvis Presley. That previous summer, Elvis paid the sum of $3.98 (plus tax)Â to record two songs for his mother. The young man made an impression on Sun producer Marion Keisker, whose studio notes read, “Good ballad singer. Hold.”

It was Keisker who was constantly after Phillips to give Presley an audition. Phillips rounded up two of his best session men, future Presley stalwarts guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black. As the audition approached, Elvis remembered “this song that popped into my mind years ago.” Phillips recognized it as Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s song. They recorded it on July 5 in one take.

Here is the original recording of “That’s All Right (Mama),” three instruments only (Presley on rhythm guitar, Moore on lead guitar, and Black on bass), published by V.A. HOSS via Vevo and YouTube:

The British Invasion

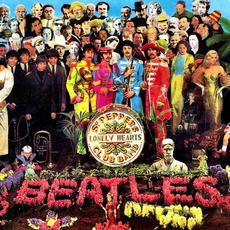

Rockabilly heavily influenced up-and-coming British musicians in the late ’50s and early ’60s. British bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones began structuring their lineup similar to rockabilly bands with lead and rhythm guitars, bass, drums, and vocals. The Rolling Stones’ early hit, “Not Fade Away” was a Buddy Holly creation.

It is known that John Lennon and Paul McCartney first met in a school auditorium on July 6, 1957. John was scheduled to play with his Quarrymen Skiffle Group while Paul looked on. After the performance, a mutual friend made the introduction. According to This Day in History:

Then Paul pulled out the guitar he was carrying on his back and began playing Eddie Cochran’s “Twenty Flight Rock” and Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-a-Lula.” A young man not easily astonished, John was astonished…Soon, Paul was teaching a rapt John how to tune his guitar…

Yes, the same Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent who three years later would be involved in the London taxicab accident. As Bill Haley & His Comets sang in 1953, “Crazy, Man, Crazy.”

Coda

Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup wrote “That’s All Right (Mama)” in 1946. He signed over the copyrights of his music to his manager, which was common practice at the time. Crudup left music in the ’50s to work on farms in Virginia picking fruits and vegetables. He died in 1974.

In 1971, Downbeat magazine estimated that Crudup should have earned $250,000 ($2 million today) for “That’s All Right (Mama)” and another song recorded by Creedence Clearwater Revival. Crudup never saw a penny. After his death, his family received an undisclosed sum from the music publisher who owned the copyrights.

The commonwealth of Virginia announced plans to install a highway marker honoring Arthur Crudup on its Eastern Shore.