John Fogerty’s Creedence Gig Was the Best of Times, Worst of Times

After leading the most popular band in America, Fogerty ended up in court accused of plagiarizing himself.

Bob Dylan’s Advice

On February 9, 1987, John Fogerty found himself onstage to jam with the likes of Bob Dylan, George Harrison and Taj Mahal at the Palomino, a nightclub in LA.

It had been 15 years since Fogerty’s band, Creedence Clearwater Revival, called it quits after a glorious run in which the band sold 28 million records in the US alone.

Significantly, Fogerty maintained his self-imposed ban on performing any of those ubiquitous Creedence songs that still populate radio playlists on every corner of the earth. Having lost ownership rights to his song catalogue, Fogerty simply refused to pay royalties to the villainous Saul Zaentz of Fantasy Records (more about this soon).

Somebody overheard Bob Dylan telling Fogerty, “Hey, John, if you don’t do these tunes, the world’s going to remember ‘Proud Mary’ as a Tina Turner song.”

It wouldn’t be until a 4th of July benefit concert for Vietnam veterans that Fogerty took Dylan’s advice. Fogerty soon wrote in his autobiography, John Fogerty: an American Son, that “Dylan certainly put the bee in my bonnet.”

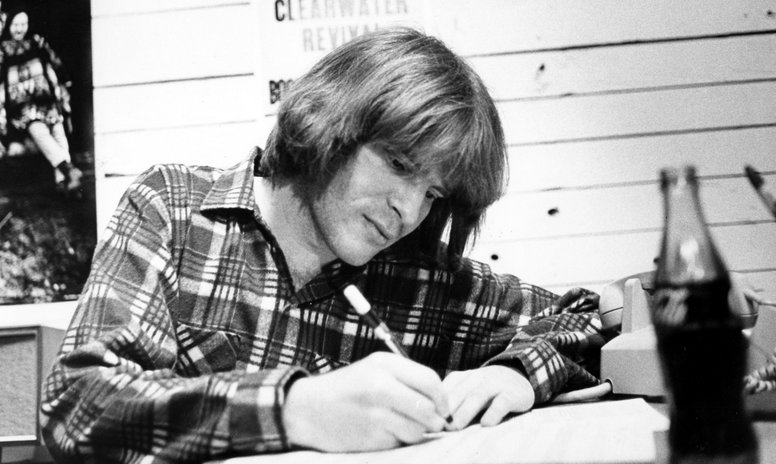

Top of the Pops

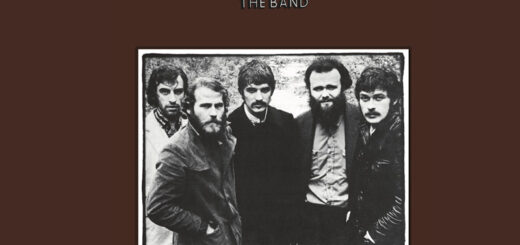

For two triumphant years, 1969 and 1970, Creedence Clearwater Revival was the most popular band in America. The band was a hit machine. You couldn’t go an hour without listening to one of its songs on the radio.

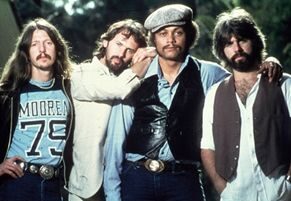

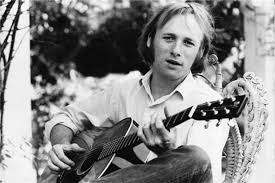

Even though John Fogerty, his older brother Tom Fogerty (rhythm guitar), Stu Cook (bass) and drummer Doug Clifford hailed from El Cerrito, CA, basically a suburb of San Francisco, the band eschewed the psychedelic vibe of its Bay Area neighbors like the Grateful Dead or Jefferson Airplane.

Rather, CCR’s musical style came to be known as “swamp rock,” with elements of the blues and rockabilly, and lyrics summoning bayous, catfish, “green rivers” and other symbols of the Southern US. A first-time listener could reasonably assume that the band originated in Louisiana.

Rolling Stone writer Ellen Willis made this astute observation:

Creedence never crossed the line from best selling rock band to cultural icon… [John Fogerty] had no affinity for the obvious image-making ploys: flamboyant freakery, messianism, sex, violence. Nor was he a flashy ironist. Instead, he reflected intelligence, integrity and moderation.

Ellen Willis

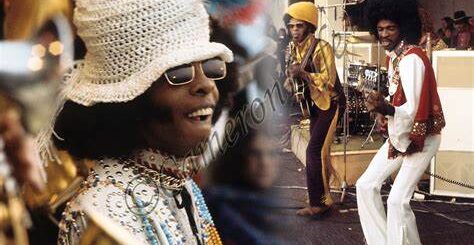

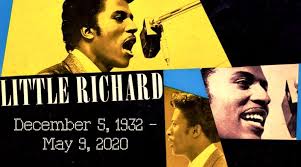

After the 1968 song “Susie Q” broke through the Top 40 charts, Creedence began its radio domination with hits such as “Born on the Bayou,” “Fortunate Son” and “Bad Moon Rising,” culminating in its first number-one single, “Proud Mary,” which was eventually covered by over 100 artists, most notably Ike & Tine Turner in 1971.

Here is a three-minute video of “Proud Mary,” published by Creedence Clearwater Revival via YouTube:

Creedence Goes South

As with most rock band, internal disputes and greedy record companies both take their toll on a band’s morale and longevity. Older brother Tom Fogerty demanded more collaboration within the group, which John Fogerty found laughable:

I was alone when I made the [Creedence] music. I was alone when I made the arrangements, I was alone when I added background vocals, guitars and other stuff. I was alone when I produced and mixed the albums. The other guys showed up only for rehearsals and the days when we actually made the recordings…I was the one who created all this.

John Fogerty

Tom Fogerty quit the band in 1972.

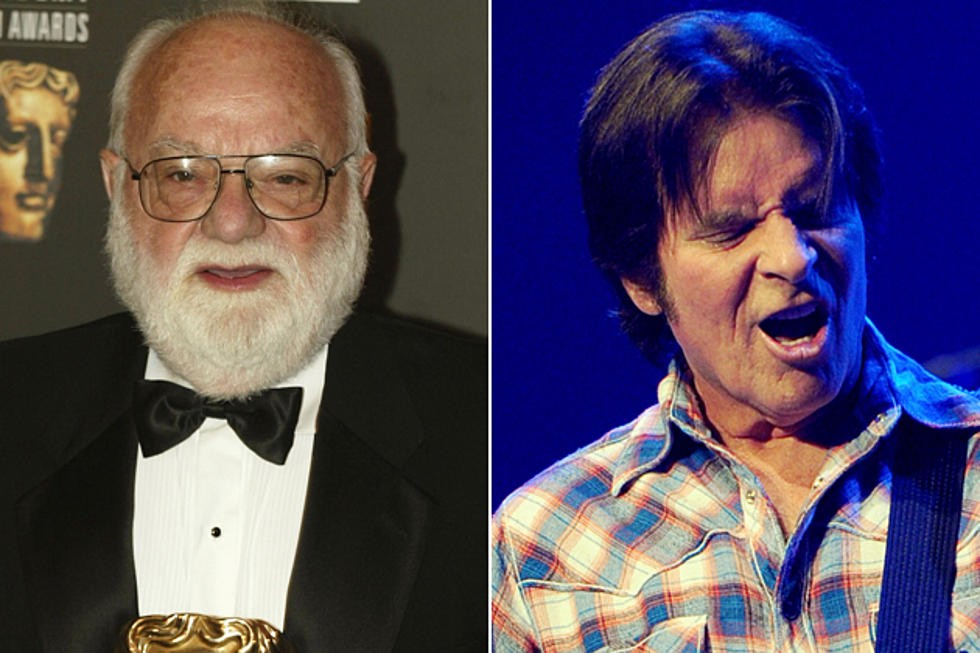

For John, it wasn’t that easy to walk away. Not only had he signed away the ownership rights to all of his songs. Fogerty also found himself eyeball to eyeball with Fantasy Records owner Saul Zaentz in an obscure corner of copyright law.

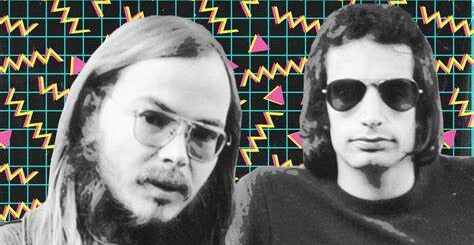

John Fogerty’s solo career, sans the Creedence hits, hit a zenith in 1985 with the chart-topping album Centerfield. Aside from the title song, Fogerty made a score with the song, “The Old Man Down the Road.”

Zaentz sued Fogerty with the claim that “The Old Man Down the Road” was simply a rewrite of a 1970 CCR song over which Zaentz held copyright ownership, “Run Through the Jungle.”

Basically, John Fogerty was being sued for plagiarizing himself.

Saul Zaentz also was not amused that one song on the Centerfield album was titled “Zants Can’t Dance.” He filed a separate defamation suit.

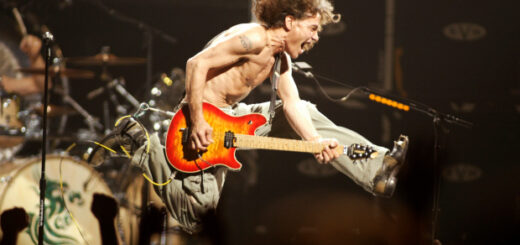

In a memorable rock ‘n’ roll moment, Fogerty went to court with guitar in hand to demonstrate the difference between the two songs. The jury ruled for the defendant Fogerty.

As for the defamation action, Fogerty wisely change the lyrics from Zants to Vants.

The Songs “Come Home to Daddy”

Creedence Clearwater Revival made Saul Zaentz a pile of money. It allowed him to be executive producer of several high-profile Hollywood movies. In 2004, Zaentz sold Fantasy to Concord Records.

In a goodwill gesture, Concord restored John Fogerty’s ownership rights to his songs.