The Legendary John Hammond

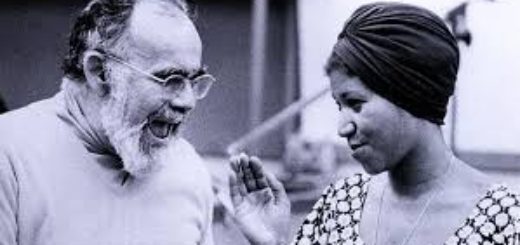

Innovative producer Hammond was also a talent scout, civil rights activist…and father to blues musician John P. Hammond.

Jazzman

When name-checking the pioneers of rock ‘n’ roll, it would seem John Hammond doesn’t immediately come to mind. Preference is often given to performers over those toiling behind the scenes, even a tastemaker such as Hammond, acclaimed as a major influence on recorded popular music in the 20th century.

It’s not that Hammond couldn’t have become a performer. Born to a socially prominent New York family with relatives named Vanderbilt and Sloane, John Hammond started playing the piano at age four before switching to the violin at eight. But he was drawn to the rhythmic sounds emanating from the family’s servants’ quarters that set him on a career path. The man fell in love with jazz.

The ’30s

Hammond bucked a family tradition by dropping out of Yale in 1931 for a career in the music business. From his perch as an A&R man for Columbia Records, Hammond met the great Benny Goodman and played a role in organizing Goodman’s jazz orchestra. Hammond convinced Goodman to hire Black musicians such as Charlie Christian, Lionel Hampton, Fletcher “Smack” Henderson, and Teddy Wilson. By 1934, Goodman’s band was the most successful musical ensemble in America.

Hammond and Goodman were known to take nocturnal jaunts to Harlem to buy records and spot newcomers. On one such occasion, they heard an unknown 17-year-old Billie Holiday and Hammond was smitten. He arranged for Holiday to record with Goodman and she broke through. Hammond’s affinity for finding raw talent was now bearing fruit.

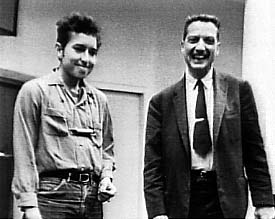

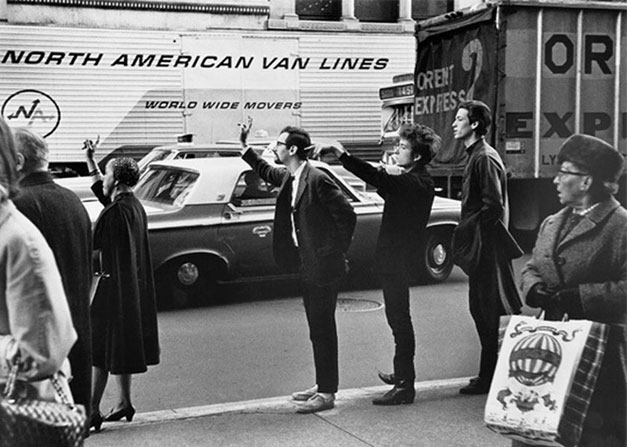

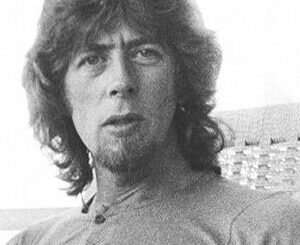

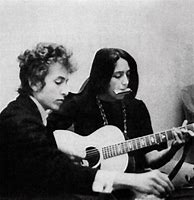

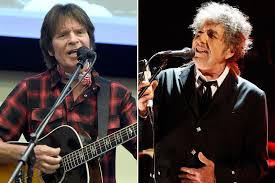

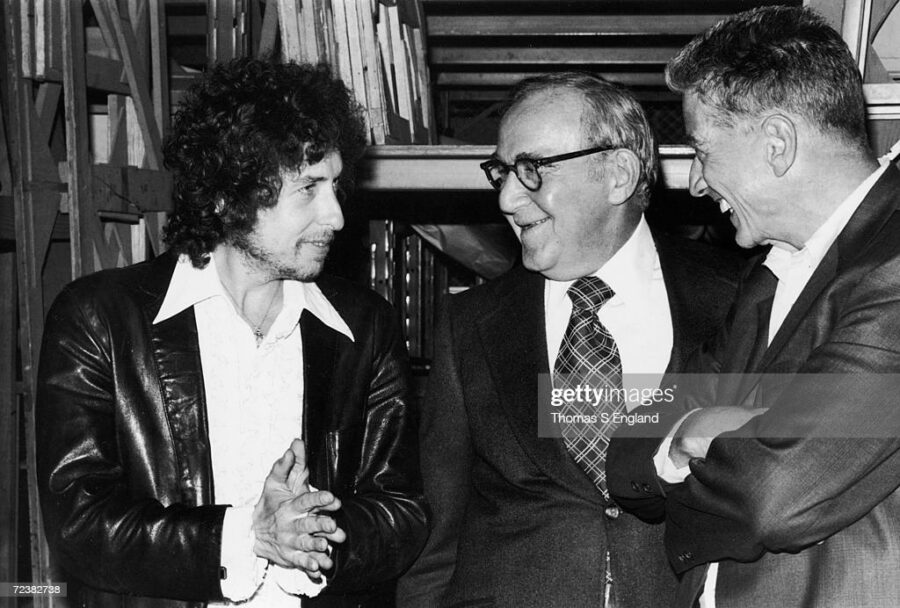

Bob Dylan, Benny Goodman & John Hammond during a TV tribute to Hammond. Photo by Thomas S. England/Getty Images

Talent Scout

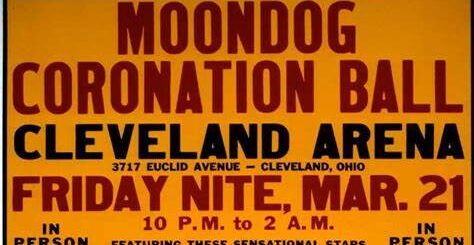

In his travels, Hammond’s discoveries were like notches on his belt: listening to Count Basie on an obscure Kansas City radio station; finding guitarist Charlie Christian in a honky-tonk club outside Oklahoma City; and organizing in 1938 a Spirituals to Swing concert at Carnegie Hall that put the likes of Big Joe Turner, Meade “Lux” Lewis, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Big Bill Broonzy, and Sonny Terry in the Big Apple spotlight.

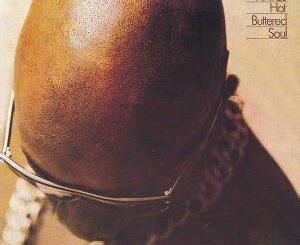

After serving in World War II, Hammond, eschewing the post-war bebop jazz scene, signed Pete Seeger and an 18-year-old gospel singer named Aretha Frankin (who actually found her form after moving to Atlantic Records). And then there was Bob Dylan.

Dylan Signs with Columbia

In 1961, John Hammond by chance listened to Bob Dylan play harmonica during a session for folksinger Carolyn Hester, whom Hammond had signed the previous year. Hammond was intrigued and signed the unknown Dylan to a Columbia contract. The suits howled in unison, referring to Dylan as “Hammond’s Folly.”

In a 1968 interview with Pop Chronicles, Hammond shed some light on his production instincts:

What I wanted to do with Bobby is just get him to sound as natural, just as he was in person, and have that extraordinary personality shine through…Afer all, he’s not a great harmonica player, and he’s not a great guitar player, and he’s not a great singer. He just happens to be an original. And I wanted to have that originality come through.

A big notch on his belt.

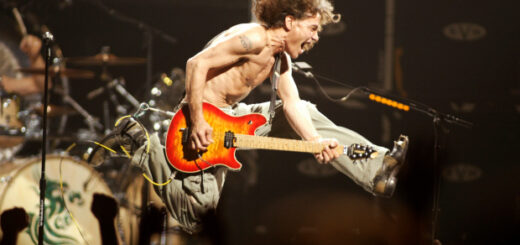

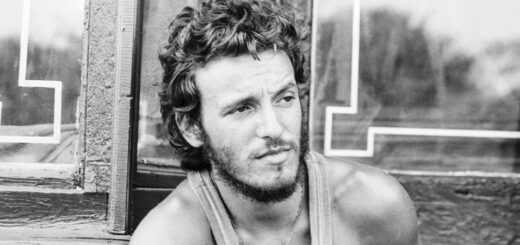

Bruce Springsteen

A decade plus one year later, Hammond signed another luminous rock act, Bruce Springsteen (though it’s fair to point out that Columbia president Clive Davis did some of the early heavy lifting). On May 2, 1972, a skinny, 23-year-old Springsteen, carrying a beat-up acoustic guitar and accompanied by his manager Mike Appel, auditioned in Hammond’s office.

“John later told us that he was poised and ready to hate us,” Springsteen wrote in his book, Born to Run. “But he just leaned back, slipped his hands together behind his head, and smiling, said, ‘Play me something.'”

Bruce slung his guitar in place and sang, “It’s Hard to be a Saint in the City.” The producer stopped him at various points in the song and asked him to repeat certain lyrics. Bruce complied. When the song was finished, Hammond was smiling and said, You’ve got to be on Columbia Records.”

“One song, that’s all it took,” Springsteen wrote.

The rest, as they say…

Civil Rights Activist

When John Hammond committed to jazz, the integration of its bands and venues had not yet begun. Hammond spent his lifetime breaking down barriers between Black and white. “One of the reasons I’m the way I am is that I got to know Harlem,” Hammond said in 1971. “Upperclass white folks went up to Harlem in the ’20s, slumming. I went out of passion. Anyone who did that had his life changed.”

His efforts to integrate Benny Goodman’s and other jazz orchestras testify to his activism. Hammond used his inherited wealth to fund the recordings of unsigned budding Black musicians, starting in 1931 with Garland Wilson.

The Son Also Rises

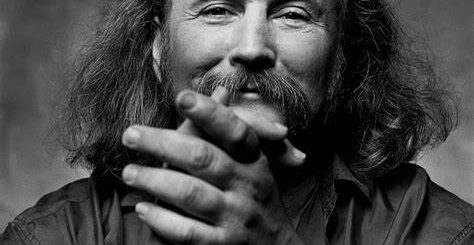

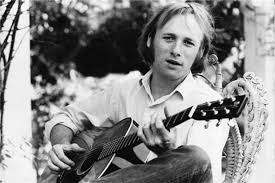

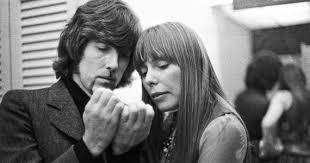

John P. Hammond, the ‘P’ for Paul Robeson, the famous singer and civil rights activist, grew up in the formidable shadow of his father but John P. didn’t seem to mind. It must have been a blast to be the one to advise Bob Dylan on backup musicians and recording studio politics. “Bob always looked to me for guitarists,” John P. recalled for the New York Times.

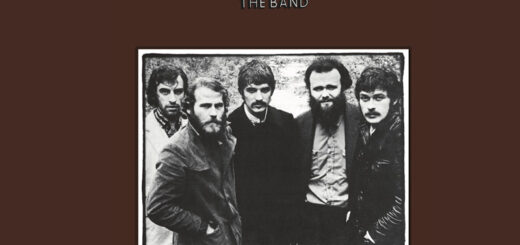

John P. perhaps channeled his father’s legendary knack for finding talent by being in a Toronto bar watching a band called Levon & the Hawks and beckoning them to come to New York to play on his upcoming album and perhaps audition for the big boys.

That Toronto ensemble, who would eventually call themselves The Band, traveled to New York to play on John P.’s fourth blues album, So Many Roads. The album was one of 34 John P. released to critical acclaim.

After So Many Roads, John P. recommended his studio players to Bob Dylan. No doubt Dad was very proud.

Coda

John Hammond was inducted into the inaugural (1986) class of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. He received the Ahmet Ertegun Award for “his critical role in integrating the music industry.”

He died on July 10, 1987, at age 76.