Liberal Educator Horace Mann’s Last Triumph: Antioch College

The ‘father of the common school’ journeys to Yellow Springs, Ohio, to lead the ‘Harvard of the West’

How would it have been for Horace Mann in September of 1853, traveling west from Massachusetts to Ohio, the excitement over his future at Antioch College making conversation even more lively over the clatter of hoofbeats clicking on the road?

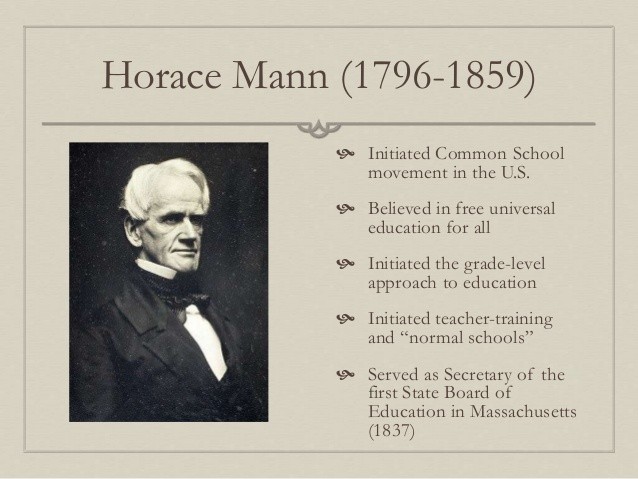

Horace Mann, born in 1796, was known in Massachusetts as a Whig politician specializing in promoting and reforming public education. Mann served in the state legislature for two tenures: 1827 to 1837, and 1848 to 1853 (the seat previously held by John Quincy Adams). In between, he was secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education.

Education For All

For his service on that board, Mann could tally his accolades: America’s Educator. Father of the Common School. Why would Horace Mann abandon such adulation to travel on difficult terrain to a destination not even on most maps? Perhaps he saw a unique opportunity.

About Mann’s progressive vision, historian Ellwood P. Cubberly had this to say:

No one did more than he to establish in the minds of the American people the conception that education should be universal, non-sectarian, free, and that its aims should be social efficiency, civic virtue and character, rather than mere learning or the advancement of sectarian ends.

Ellwood P. Cubberly

Antioch College Comes Calling

When Mann returned to the state legislature in 1848, he knew his heart was not in politics. He turned down the Free Soil Party’s nomination to run for Massachusetts governor. Instead, Mann accepted the offer of the presidency of the newly formed Antioch College.

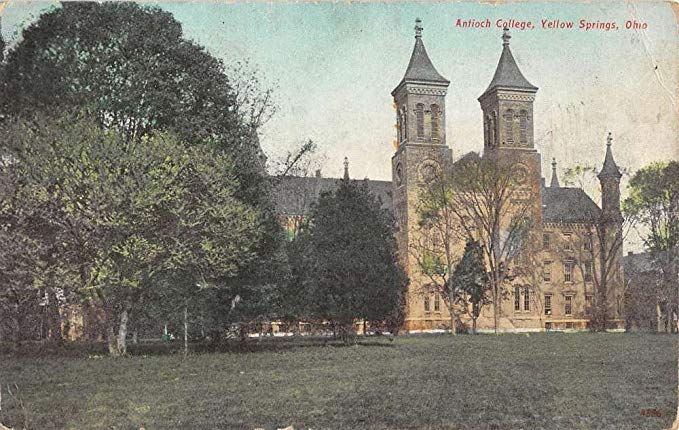

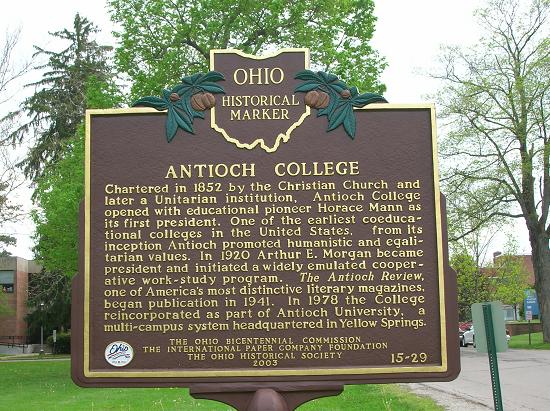

Antioch College (named for the great Syrian city from which Paul the Apostle set out on missionary journeys) landed in Yellow Springs after some intense bidding by several Ohio towns. Yellow Springs, a small resort stop between Dayton and Springfield, joined over 26 other Ohio colleges, “all small and all sectarian.”

In recruiting Mann to be president, the first Trustees seem to have shared Mann’s reformist vision by promising to: 1) admit all students without discrimination, 2) ensure that women faculty be on par with men, 3) promote character to be as important as academic proficiency, and 4) minimize the importance of grades. The Trustees also assured Mann that Antioch would be non-sectarian, a promise that would be tested vigorously.

Mann was offered $3,000 a year. Even though he could have easily made that in lecturing or law, Mann accepted.

A Rocky Start

Horace Mann arrived in Yellow Springs in September 1853. Setbacks greeted him immediately. His furniture and most of his books were lost en route: thrown from his coach to the bottom of Lake Erie. No house had been built for him as promised. Mann and his wife Mary had to endure many weeks in a boarding house. Mann was informed that his salary was reduced to $2,000, and subsequently downgraded to $1,500 for his first year.

Despite all that, Mann refused to relinquish his optimistic glow. “I can endure anything for the sake of these young people!” he exclaimed.

The Harvard of the West

Once settled, Mann went about the task of making Antioch “the intellectual opening of the West.”He designed the school’s curriculum after that of Harvard University, emphasizing “physical and moral health,” along with rigorous course selection.

Immediately, Mann and the Trustees were at odds over the admittance of a black person (this was nine years before Emancipation). Mann was steadfast; this was a condition of employment. And so, even as the president of the Board of Trustees, Judge Aaron Harlan, resigned in protest, the first black student was admitted to Antioch…a truly historic occasion.

Turbulence and Enlightenment

In the scheme of things, race relations were a minor source of conflict. Two other issues loomed much larger: the school’s financial condition and the initial vow to keep Antioch non-sectarian. It was said that some influential trustees intended Antioch to be a Christian college all along.

The battle over sectarianism spread like wildfire to faculty, students, and even the local townspeople. Sides were taken. Soon the campus rang out with pro- and anti-Mann factions. Many were suspicious of Mann’s liberal views.

In the end, though, Horace Mann prevailed. His contract was renewed each year, and Antioch remained non-sectarian. It is today.

As the campus life returned to normal, a certain enlightenment was in the air. For example, Antioch’s dining room accommodated both sexes. Mann wrote that it was a “charming scene of social enjoyment and innocent hilarity”–unlike Oberlin College, where students were not allowed to speak during meals.

Countless Financial Crises

But while there was hilarity in the dining hall, big trouble was brewing inside the majestic brick towers that housed Antioch’s administrators. The reason, obviously: the school was virtually bankrupt from the time it opened its doors.

Mann had to have known this: all he had to do was sit down and do the math (not his favorite subject). He soon discovered that most students were on scholarship and that room and board was priced so low that it barely broke even.

In June 1856, the Board of Trustees reelected Mann president and voted to keep the college open, no matter what. Several Trustees pledged money to cover the deficit. Tuition was raised to $24 per year.

Another Crisis Averted

Those valiant efforts had little effect. By Spring 1858, the debt had grown to $83,000. Mann himself stepped forward to pledge $5,000. Perhaps because of Mann’s generosity, pledges were paid in full. Another crisis was averted.

To this day, financial crises similar to those in Horace Mann’s day have become a daily part of Antioch’s cultural life. It wouldn’t be Antioch without the latest news of some anonymous donor pulling the school out of the fire.

“Be Ashamed to Die…”

The last predicament of Mann’s reign came with a severe cost: the president himself.

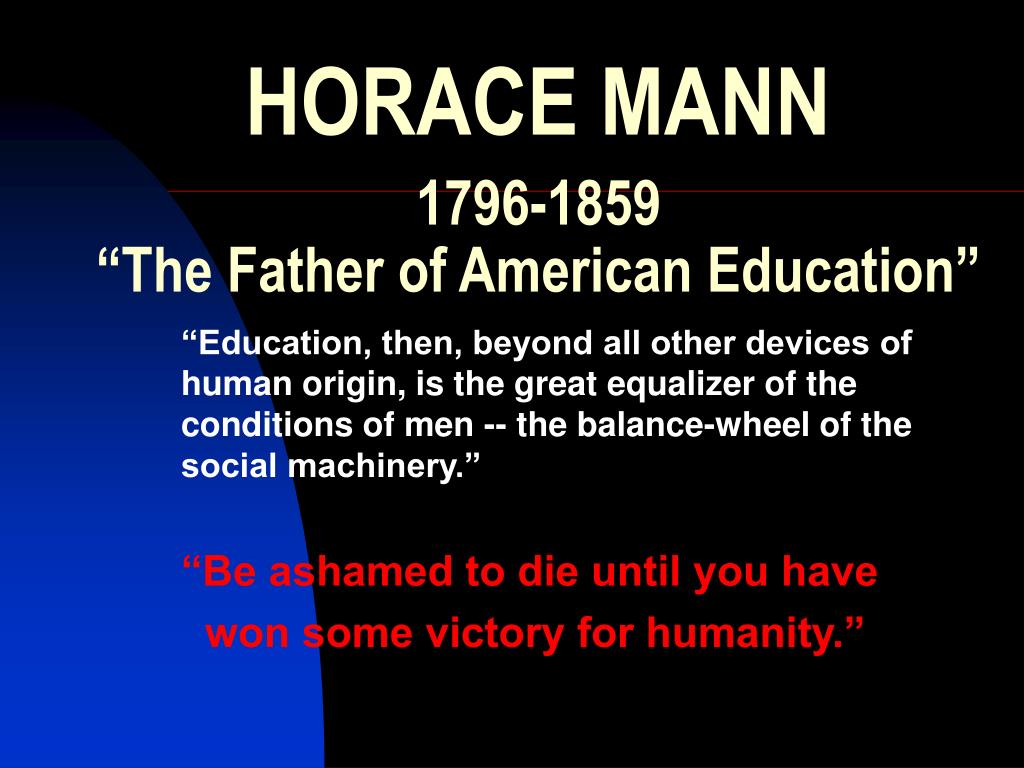

Mann’s health, always delicate, diminished by the spring of 1859. Despite his health, and despite Mann’s futile effort to resign for the good of the school, Mann was unanimously reelected president. He mustered the energy to give the Class of 1859 a commencement speech that history will judge as one of the greatest. It included the famous beckoning:

Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.

Horace Mann

With the Ohio summer heat consuming him, Horace Mann succumbed. He died on August 2, 1859.

Antioch Lives!

Antioch College closed its doors on June 30, 2008. That previous year, Antioch was in a state of flux as its many stakeholders failed to agree on a formula to separate the college from its parent Antioch University, the complexities of which won’t be covered here.

But there was always a plan to reopen. A task force was gathered to create an independent Antioch College. The college mustered its assets and reopened in the fall of 2011. The graduating class of 2016, its first since 2008, conferred degrees on 21 students. Antioch’s undergraduate enrollment numbered 127 full-time students in 2024.

Horace Mann would have been proud.

Disclosure: the author attended Antioch College during the years 1975-77. He was editor of the Antioch Record.