Pension Funds Abductions Would make a Jailed Mob Boss Proud

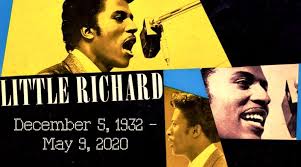

The ongoing efforts by conservative groups to weaken public pension funds would probably coax a smile from former Philadelphia/South Jersey mob boss Little Nicky Scarfo’s snarling lips.

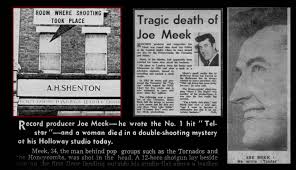

You might remember that it was Scarfo, in his 1980’s heyday, who plundered the Health and Welfare Fund of the Hotel Employees Restaurant Employees (hereafter known as “Bartender’s”) Local 54 in Atlantic City, NJ, an integral part of the mob boss’s territory. (Let’s put to rest right now that a Health and Welfare Fund serves a different purpose from that of a union’s Retirement or Severance Fund. But they are all funded by the hard-earned contributions of workers, whose expectations of a just reward are slapped down.)

It was said that Little Nicky pocketed at least $20,000 a month from Local 54, even directing payments from his jail cell, before federal prosecutors came calling in 1990. More about this later.

For Scarfo, it was all about personal gain. For conservatives and their legislative cohorts, it has to do with ideology and with pleasing their Wall Street patrons. The latter is more than a rhetorical jab. A case in point: In an op-ed debate on pension funds in the New York Times last week, it was reported that New York City’s pension fund, which controls $200.4 billion in assets, pays a total of $472.5 million to various wealth-management firms on an annual basis. “Fees have gone up in fact because [New York] has put more and more of its public pension fund assets into expensive investments run by hedge funds and private-equity funds,” wrote Nicole Gelinas in the op-ed piece.

Whether it’s those fees to Wall Street firms or the preservation of corporate subsidies and tax cuts, there’s a certain conservative narrative on the march that holds that a) public employee pensions are a risk to state and local budgets, b) nationwide, public pensions are underfunded by trillions of dollars, and c) public employee pensions are much more generous that those paid in the private sector. And for every serious-sounding conservative narrative, there appears a special interest group or two, cloaked in silk-suited respectability, that offer familiar remedies that might entice at first glance.

ALEC Comes Calling

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) has jumped into the pension fund fray by making its diminishing a top 2014 legislative priority. ALEC is offering its “model policies” to sympathetic state legislators that would convert public pension funds from “defined benefit” plans to “defined contribution” plans. First, some definitions, culled from Wikipedia:

* A defined benefit plan “calculates benefits using a fixed formula that typically factors in final pay and service with an employer, and payments are made from a trust fund specifically dedicated to the plan.”

*The defined contribution plan accrues benefits “solely attributable to contributions made into the account and investment gains on those funds, less any losses or expense charges. The contributions are invested (e.g. in the stock market) and the returns on the investment are credited to or deducted from the individual’s account.” This is similar to a 401(k) plan or an IRA that are a staple in the private sector.

The results have been mixed, to put it generously. Alaska and Michigan converted to defined contribution plans and saw their pension fund deficits increase, according to the National Pension Fund Coalition. In Rhode Island, costs were escalated so much by fees to money-managers that even Forbes Magazine called it “just blatant Wall Street gorging.” And then there’s the case of West Virginia.

West Virginia converted to a defined contribution plan for its public employees in 1991, but switched back in 2006, according to the book Plot Against Pensions, when it was found that “public employees had such low incomes in retirement that they were eligible for means-tested public programs [like food stamps], driving up costs to the state.”

Public pensions do face an annual shortfall of about $46 billion. That seems to be the battle-cry of a partnership between the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Retirement Systems Project and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. This partnership has been working in tandem across the country to sound the alarm of an imminent pension fund crisis: $46 billion unfunded annually! A 30-year shortfall of $1.38 trillion! That’s a lot of zeros for a state legislator to digest.

John Arnold, by the way, is a billionaire conservative activist who has some experience with slashing pension funds: His company, the infamous Texas oil company Enron, went bankrupt over 10 years ago over a massive scheme of “cooking the books.” The collapse of Enron decimated the pension funds of its workers.

Local Governments’ Desperate Dilemma

The pension fund shortfall is a reality that state and local governments cannot shrink from. Budgets must be balanced. With the conservative echo machine blaring daily, pension funds have become easy targets, as states compete with other states, cites compete with towns and surrounding suburbs, with competition even reaching across oceans and continents…all to lure companies to their localities, with the promise of jobs and an expanding tax base. This is not without consequence.

An exhaustive New York Times investigation revealed that states, counties and cities are giving away more than $80 billion to companies in the form of subsidies and tax breaks. These incentives come in many forms, according to the Times: “cash grants and loans; sales tax breaks; income tax credits and exemptions; free services; and property tax abatements.” It all adds up to $80 billion annually. Remember the $46 billion pension fund shortfall? I’ll let you do the math.

The siren’s call to cut public employees’ pensions seems to have carried the day in Illinois. The state, burdened with one of the country’s most troubled state employee pension fund, with an unfunded liability reaching $100 billion, may have created a blue state template by cutting retirement benefits after a bitter legislative battle. The law would cut cost-of-living increases, cap the salary level used to calculate pension benefits, offer an optional 401(k) plan to those willing to leave the system and raise the retirement age of younger workers by as many as five years.

According to Huffington Post, “All [Illinois public employees] had faithfully made their required contributions to the state’s pension fund for years, even though the legislature failed to make the required payments so it could avoid raising taxes on the state’s wealthiest citizens.”

Promises Made, Promises Broken

As the news of Detroit’s bankruptcy sunk in all over the country, perhaps Illinois’ state workers, while feeling used and abused, were thanking their lucky stars. At least they would have retirement benefits. In responding to a US bankruptcy judge’s question about what he would say to a Detroit retiree, Detroit’s Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr was brutally frank: “I would say that his rights are in bankruptcy now.”

Orr claims that the city’s pension system is a $3.5 billion part of Detroit’s approximate $18 billion debt. As this story drags on, there is no restful sleep for the Detroit police officer or sanitation worker approaching retirement.

Nor for workers in the private sector. Increasingly for them, pensions have become a thing of the past. The Bureau of Labor Statistics sounded the bad news: Only 18 percent of all private-sector workers enjoy pension coverage, down from 35 percent in the early 1990s. The BLS study revealed that unionization was a key factor in gaining retirement benefits. “Pension coverage is much higher in the public sector (78 percent) and among unionized workers (67 percent) in the private sector. In contrast, only 13 percent of non-union private-sector workers are covered,” according to the study.

The size of the private-sector establishment plays a role in pension coverage. For businesses with 500 or more workers, 48 percent offered some kind of pension…compared to only 8 percent of businesses with 50 or fewer employees. Again, unions are a positive factor here. In unionized industries such as construction or transportation where small businesses use multi-employer plans, pension coverage is comparatively high.

‘Union Boss’ Scarfo’s Comeuppance; Bartenders Triumph

The infiltration and plundering of Bartenders Local 54 in Atlantic City was more than just a money-grab by mob boss Little Nicky Scarfo and his henchmen. It codified a culture of corruption that contaminated everything in its path, from union members’ activities, the treatment of vendors and competitors… all the way up to the mayor’s office.

Phillip Leonetti, Scarfo’s nephew and “underboss” who turned informant, said in a sworn statement, “No appointments, jobs, union cards or other favors were made or given without Scarfo’s approval.” Aside from the monthly payments of $20,000, Leonetti and other informants say Little Nicky used his union position plus fear and intimidation to extort payments from various Atlantic City restaurants to remain union-free. It’s safe to say that Scarfo never paid for a meal in an Atlantic City restaurant.

Remarked federal investigator James Flanagan, who had monitored Local 54 in its dark days, “It was not run with the members in mind.”

To top it off, federal authorities charged that when Local 54 official Albert Daidone and mobster Raymond “Long John” Martorano were on trial for the murder of roofers’ union leader John McCullough because allegedly McCullough was attempting to grab control of the bartender’s union local from Scarfo, $175,000 was embezzled from the union’s benefit fund to pay for legal fees.

The culture of corruption eventually found its way to the mayor’s office. When he was elected mayor of Atlantic City in 1982, Michael J. Matthews met privately with Leonetti and other Scarfo associates…perhaps to express his gratitude for the bulging envelope containing $125,000 in campaign cash. Matthews, originally from small-town Pennsylvania and with a business degree from American University, found himself in Scarfo’s pocket, and decided to make the best of it. The mayor turned a blind eye to the restaurant shakedowns and to various shady real estate transactions that were made in the midst of creating Atlantic City’s casino skyline. While under federal investigation, it was found that Matthews had close dealings with Scarfo for years before he was elected mayor; their go-between was Local 54 organizer Frank Lentino. Matthews was formally charged with extorting $668,000 from two Atlantic city businesses and taking $14,000 in bribes from an undercover FBI agent. Voters recalled him in a 1984 referendum. In 1985 Matthews was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison. He was paroled in 1990.

Endgame

1989 – Scarfo is sentenced to 14 years for extortion and 55 years on RICO charges. It is tantamount to a life sentence.

1990 – US Attorney General Dick Thornburgh files a sweeping federal anti-racketeering suit against Bartender’s Local 54, seeking a government takeover of the union. All union officers handpicked by Scarfo are fired.

1995 – UNITE (the Union of Needletrades, Industrial & Textile Employees) is formed in a merger involving two old-time textile unions.

2003 – UNITE and the Hotel Employees Restaurant Employees Union (HERE) work together on the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride and other organizing actions.

2005 – HERE and UNITE merge to form UNITE-HERE. The union would settle contracts for over 60,000 workers in 400 hotels in North America.

And in 2012, members of UNITE-HERE Local 54 voted overwhelmingly to approve a new three-year contract with eight Atlantic City casinos. Among the provisions that are being enjoyed by the 14,000-member local: a continuation of free health care and the preservation of its employer-sponsored defined benefit pension plan.

Local 54’s storybook ending can make you feel that good things can happen for people who play by the rules. For Detroit retirees, for public employees in each and every state, and for workers everywhere who want a secure retirement, it will also require a little bit of pluck.

My advice to them: Fight for what’s yours.