Their Business Model Shattered, Alternative Weeklies Face Finale or Reset

Here in Philadelphia, for those of us who love and admire the truth-telling in good journalism, venturing to our local street corners to retrieve our free weekly newspapers has turned into a heart-breaking ritual. Both papers–the Philadelphia Weekly on Wednesdays and the Philadelphia City Paper on Thursdays–have become so thin that they feel, well, almost insignificant when you hold them in your hands. And that’s a real shame.

In their primes, both papers thrived in a media market that permitted two alternative news/entertainment weeklies (hereafter called alt-weeklies) to compete in a newsprint version of the clash of the titans…a rare occurrence outside of New York City. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the Weekly and City Paper were flush with pages (easily over 100 each), advertising (sex classifieds and real estate ads were big money-makers), cutting-edge local stories, must-read music and restaurant reviews and syndicated columns that had national followings.

And then came the internet, and it was all over. Well, almost. The most recent copy of the Weekly comprises 36 pages (including an impressive nine pages of real estate ads); the City Paper, 40. The problem here is obvious: alt-weeklies are dedicated to young people…the same young people who are conjoined to the internet from birth, and who simply don’t read newspapers. In that regard, alt-weeklies are actually worse off than traditional daily newspapers, because at least older folks don’t mind getting a little newsprint on their fingers.

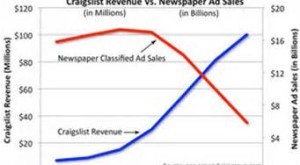

The undernourishment of Philadelphia’s alt-weeklies has everything to do with their only revenue stream: advertising. On the one hand, according to the online newsletter e-Marketer, total media ad revenues are expected to grow between 3-4 percent annually through 2017 (though primarily benefiting TV). On the other hand, e-Marketer reveals: “Spending on digital advertising…will total $42.26 billion this year, or nearly one-quarter of all ad dollars. This is up 14.9% since 2012.” This is not a recipe for print media growth.

So why don’t these two Philadelphia papers join forces and attempt to survive as one? In an article in Philadelphia Magazine published in May 2012, writer Jason Fagone breaks it down:

It seems pretty obvious that there won’t be two print weeklies in Philadelphia for much longer. For one to survive, the other has to die–or agree to merge. Either way, something drastic has to happen. But right now, there’s an eerie sort of stalemate. The two papers are limping along, losing pages and advertisers and staffers, shadowboxing with each other for a prize that may not even exist anymore….Today, they’re owned by two secretive corporate suits, rich men who are as establishment as you can get–the sort of people the alt-weeklies made their reputations taking down.

Community Grounded

Almost two years later, nothing much has changed (not publicly, anyway). But what resonates here is corporate ownership. The reclusive “suits” running the show. Hmmm. Could that be part of the problem?

The irresistible strength of alt-weeklies, handed down from their predecessors in the underground press, is their groundedness to the locality they serve. It is this trait that alt-weeklies have a built-in advantage over the internet, which by its nature is “untethered to geography.” The New York Times article that provided that expression had this to say about the alt-weekly’s backbone:

An alt weekly has a staff of paid reporters and editors whose jobs are not only to know the city, but to love it, to hate it, to be an integral part of it, cajoling, ridiculing, praising and skewering city officials, artists and entrepreneurs alike, while giving voices to the “city folk.”

Alt-weeklies throughout the country have developed common devices that keep them visible in the community. Prominent among these, for example, is an annual “best of” feature, profiling businesses (restaurants especially) that readers vote best of their genre. Certificates proclaiming this achievement are distributed, and hung proudly in the business’s window. The internet hasn’t figured out a way to do things like this.

Corporate Parentage

Seemingly in direct contradiction to this quality of being community-owned and operated is an unmistakable trend in the alt-weekly business: they’re being gobbled up by larger media conglomerates which either have no connection to the community or (for example, in Philadelphia’s case), have class distinctions that don’t place them among “city folk.” A listing of all of the mergers and transactions over the past several years would be tedious (and downright depressing). Let’s focus on one of those papers, and shine a light on teachable moments for the survival of alt-weeklies.

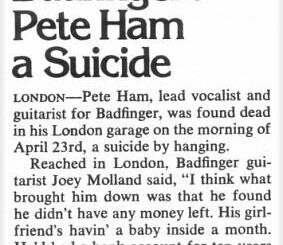

On March 14, 2013, practically a year before this publication date, the Boston Phoenix tweeted: “Thank you Boston. Good night and good luck.” It was a good run for this alt-weekly founded in 1965, but the proverbial writing was spray-painted on the wall as a life lesson for all weekly papers. In 1988, the company that owned the Phoenix, Phoenix Media/Communications Group, acquired two weeklies in smaller markets, which would become the Providence Phoenix (RI) and the Portland Phoenix (ME). There would also be a Worcester Phoenix (MA), which folded in 2000.

In 2005 the Boston Phoenix redesigned its paper from traditional newsprint to a glossy magazine format, with the intent of being “more attractive to advertisers.” Since advertisers primarily look at circulation numbers, the move to glossy seems to have had an opposite effect. The Boston Phoenix experienced the largest drop in circulation among the Top 20 alt-weeklies in 2012, falling by 29 percent. The paper folded, but significantly, the Portland and Providence papers remained intact.

Lesson #1: “Small and midsize markets have much more traction these days,” John Saltas, owner of the Salt Lake City Weekly, told the New York Times. The Huffington Post: The Phoenix‘s closing “underscored the divide between struggling big city papers and more viable smaller-market ones.”

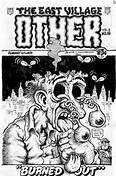

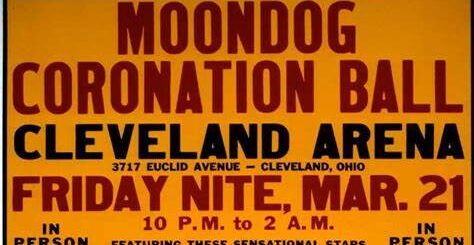

The Underground Press

For those of us who lived through it, the late sixties and early seventies were a time of bold statements and shifting alliances, usually in opposition to authority and to the established order. In Boston, a brash new “underground” newspaper was founded in a way germane to that period: by way of a two-week writers’ strike in August 1972 which, long story short, motivated two neighborhood newspapers to unite to form the Boston Phoenix. But the times demanded that it not stop there. Conflicts between writers and management split that paper in two, with the writers forming The Real Paper and management continuing to publish the Phoenix. The Real Paper folded in 1981.

In researching the underground press, those provocative, often chaotic tabloids back in the day that launched the modern-day alt-weekly, I came across a Wikipedia entry that clumsily defined the underground press as “independent (and typically smaller) newspapers focusing on unpopular themes or counterculture issues.” Unpopular themes? Now I’m thinking that the person who wrote this is either naïve or making a value judgment. But hold on. He or she might be on to something.

Back in Philadelphia, The Weekly‘s “underground” predecessor, the Welcomat, was led by former Wall Street Journal reporter turned rogue editor Dan Rottenberg. It seems Rottenberg didn’t have any money to hire staff writers so “he let his readers write the paper,” publishing letters and rough manuscripts about “race and racism, gay rights, Israel, Frank Rizzo, AIDS.” From the Philadelphia Magazine article:

Rottenberg had come to believe that the only way to improve the existing media was to embarrass them from the outside…The fact that people sued Welcomat right and left said to Rottenberg that he was doing a good job, that he was having an impact…It was all a normal part of life at the Welcomat.

In paging through current issues of the Weekly and the City Paper, it’s hard to find material that could lead to a lawsuit or even a threatening letter from an “embarrassed” subject. Granted, times have changed. Both papers are well-written and ably displayed in the conventional alt-weekly style. In the executive suites, the status quo reigns: “The problem [with ownership] isn’t that they don’t care; it’s that they care just enough to be paralyzed…” with inertia. Why rock the boat?

In Boston, the Phoenix‘s attempt to appear more “reader-friendly” by publishing a glossy magazine totally backfired. The paper no longer exists. In both cities, these teachable moments could lead us to:

Lesson #2: Be unpopular. What have you got to lose?