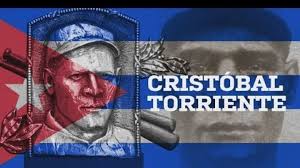

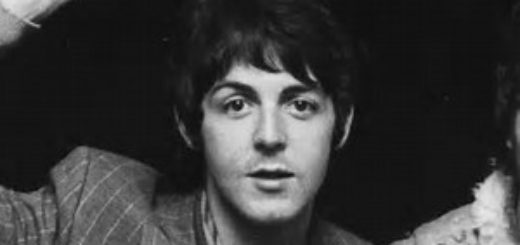

Baseball Negro Leagues: He was called the ‘Cuban Babe Ruth’

Or maybe Babe Ruth was the ‘American Cristobal Torriente.’

If I should see [Cristobal] Torriente walking up the other side of the street, I would say, ‘There walks a ballclub.’

C.I. Taylor, manager, Indianapolis ABCs

Prologue: The Negro Leagues Join Major League Baseball

Its significance cannot be overstated, especially in a profession in which statistics (“I don’t know how good he is, let me read his baseball card.”) are the primary arbiter of performance. This past December, on the 100th year anniversary of its founding, Negro League statistics–at bats, runs, hits, RBIs, wins, losses, earned run average, etc., etc.–from 1920 to 1948 will be officially classified as major league statistics.

It was indeed a positive step towards fairness and racial justice. But as ESPN pointed out, “It can never change what it did to Black players.” The deprivation of God-given talent from America’s pastime was cruel and pointless, for the fans, for the nation’s psyche and standing in the world and crucially for human beings denied the opportunity to climb to the top of their profession merely because of the color of their skin.

We’ll examine one of those human beings whose legendary exploits in the Cuban Leagues and Negro Leagues earned him the moniker, the ‘Cuban Babe Ruth.’ Or maybe the Babe was the ‘American Cristobal Torriente.’

‘There Walks a Ballclub

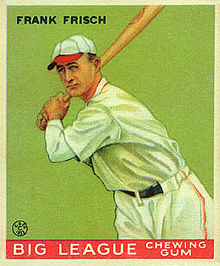

Torriente was a hell of a ballplayer. Christ, I’d like to whitewash him and bring him up.

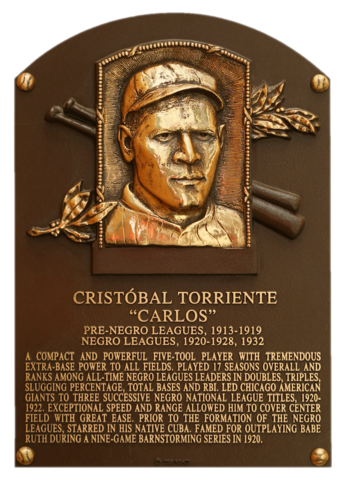

Second baseman and Hall of Famer Franke Frisch, the ‘Fordham Flash’

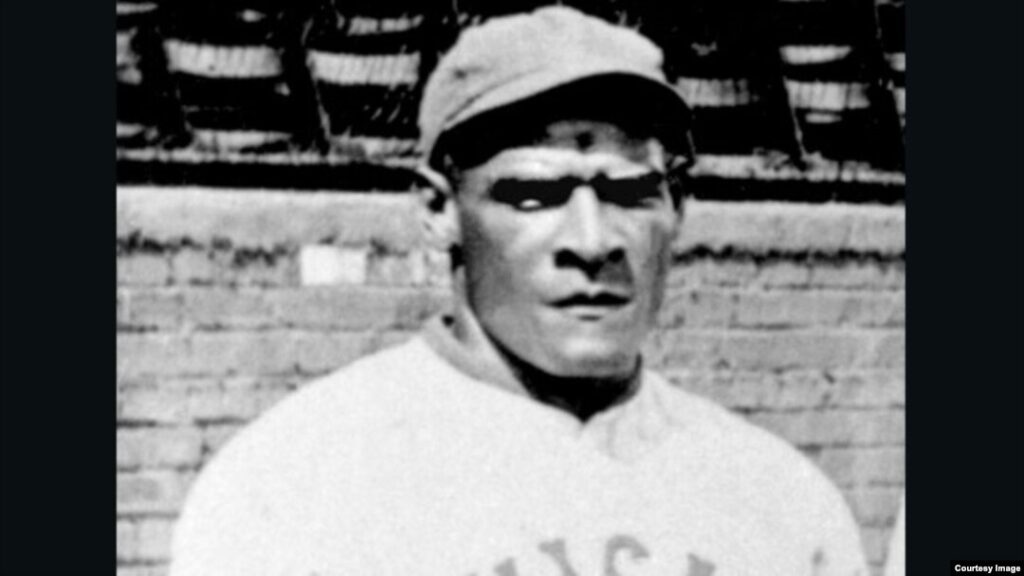

Cristobal Torriente is what baseball insiders call a “five-tool” player: He could hit for average, hit for power, field his position (centerfield); an elite baserunner who had a gun for an arm. He hit .342 in his 17 season in the Negro Leagues. He scored 540 runs and collected 404 runs batted in in just 245 games. His Wins Above Replacement is rated third of all-time in Negro League history. Torriente was known for hitting the ball hard.

Speaking of Frankie Frisch, he was playing infield in an exhibition game when Torriente hit a ball so hard that it left a small crater in the ground right next to Frisch.

“I’m glad I wasn’t in front of it,” Frisch recollected.

Torriente’s Baseball Card

Torriente spent the years 1912 to 1918 in numerous Cuban Leagues. In 1919 he moved to the Negro League Chicago American Giants, where he routinely chalked up batting averages of .324, .417, .321, .387 and .343. In Torriente’s first three seasons there, his Chicago team won Negro National League pennants.

It is just such a shame that Torriente never got to display his skills in the major leagues. But at least all of his outstanding statistical achievements will become part of the Major League Baseball record book.

“Cristobal Torriente is the best Cuban player that I’ve ever seen, the most complete before me eyes, including the Americans that came and whom I met when I went to the United States” remarked Martin Dihigo, a second baseman who along with Torriente was selected to the Negro Leagues’ all-time team.

In his final productive season in 1928, with Detroit, Torriente batted .322. He returned to baseball four years later at age 38 for one last go-round. He died six years later in New York City. He is said to be buried near his hometown of Cienfuegos, Cuba.

Barnstorming

In the fall of 1920, after the baseball season was over, Babe Ruth happily participated in the ritual of barnstorming: cobbling together show teams to play professional teams in baseball-crazy countries south of the border. It was a good source of supplemental income for major leaguers, even for the likes of Babe Ruth, long before Marvin Miller and the players union made ballplayers millionaires. (Ruth made $20,000 in 1920, a six-figure sum in today’s dollars.)

Ruth was coming off his first year as a New York Yankee after the much ballyhooed trade with Boston. The Babe hit an unheard of 54 home runs that year (he hit 59 the next), making him the most talked-about ballplayer in America.

The Babe vs. Cristobal Torriente

Ruth’s “team” sailed from Key West and arrived at the Hotel Plaza in Havana in October 1920. Onlookers gathered as Ruth’s entourage boarded a car bound for Havana’s Almendares ballfield. Ruth’s barnstorming team played at least five games against the cream of Cuba’s baseball crop.

The historical record is incomplete about what exactly transpired in head-to-head competition. It was reported that Torriente “out-homered the Bambino, 3-2, going 4 for 5 in an 11-4 win and adding a double to his homer for six RBIs on the day,” presumably day one.

At their fifth meeting, reportedly on November 6, Torriente hit three home runs, and the media attending the game were proclaiming “El Bambino Cubano.” Babe Ruth ducked out of Havana and headed for Santiago de Cuba.

“Tell Torriente,” exclaimed the Babe, “that if [he] could play with me in the Major Leagues, we would win the pennant by July and go fishing the rest of the season.”

Coda

Babe Ruth was reportedly paid $2,000 for the Havana exhibition. Cristobal Torriente was paid, according to The Cuban History website, 200 pesos, gathered when spectators passed the hat.

That’s all you really need to know about the harsh realities of the “color line,” and the inequities inherent in Negro League baseball.