Nickeled and Dimed in Saint Loo

‘Policing for Profit’ Makes for Tense Community Relations

Is Corporate State Tax Avoidance an Underlying Cause?

First off, a big fat caveat: This piece is not about the tragic death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Nor is it about alleged police brutality. And it is not about the Grand Jury decision not to indict the police officer involved, or the conduct of the prosecutor. I probably wouldn’t write about something I am a little tired of reading about.

This is about the root causes behind the unfortunate stand-off between policing authorities and the communities they are supposed to protect and represent. I am focusing on St. Louis simply because it seems to be at the epicenter of this unfolding tragedy. But it is happening mostly everywhere.

Months ago, I wrote about civil asset forfeiture and its corrosive effect on American justice and our sense of fair-play. This is very similar, but with one crucial difference: civil asset forfeiture most often preys on vulnerable people who are passing through a community. This predatory behavior that I am about to describe seeks out people who live in the community.

There are over 90 municipal governments in the St. Louis metropolitan area. This is an excessive amount and it means there are over 90 taxpayer-funded entities that require buildings, equipment, courts, police forces and other personnel. (Compare that to Kansas City on the other side of the state, whose surrounding Jackson County has just 19 municipalities.) The reasons for this dysfunctional self-governance have to do with post-Civil War migration and, yes, racial politics. Let’s leave it at that; what’s done is done. But what about the mess it has caused?

Ferguson

Yes, we all know about Ferguson, with its two-thirds minority population being governed by a white power structure, including an overwhelmingly white police force. What is less known is how this town of 21,000 residents funds its municipal operations. According to the trade publication Governing, Ferguson is “increasingly reliant on fines to fund government operations. In all, fines and forfeitures accounted for 20 percent of the city’s $12.7 million operating revenue in fiscal year 2013.”

Ferguson is by no means the worse. A total of 14 North County towns depend on traffic court fees and fines as their largest source of revenue, surpassing traditional sources such as property and sales taxes. In Calverton Park, population 1,300, the seven officers of its police force helped generate $484,000 in fines and court costs: That’s 65 percent of the town’s annual revenue. And then there’s Beverly Hills…Missouri.

Beverly Hills

The North County town of Beverly Hills is about one-tenth of a square mile. Violent crimes are rare in this town; there hasn’t been a homicide or rape in over a decade. And yet Beverly Hills, population 570, is patrolled by a police force numbering 12, which made 646 arrests last year. According to the Chicago Tribune, “court-related revenues totaled $415,000 last year, including $340,000 in fines…That provided all of the money to cover the town’s payroll and benefits.”

Besides covering a town’s payroll and benefits, where does this fine money eventually end up? And how do fines for small infractions grow so large? Broadcaster KMOV in St. Louis investigated the municipal courts in its area. It tracked an individual, a one Dustin Theabeu, who was in court to pay for two “failure to appear” fines related to one single speeding ticket. The costs compounded as follows: $100 each for the two failure to appears, plus $135 in additional court costs. Mr. Theabeu was out $335 because he couldn’t take time off from work. “It’s tough but I have to pay it,” he remarked.

KMOV-News 4 acquired a breakdown of typical court costs for North County. For a ticket for “littering from a vehicle,” the fine is $137.50. But there’s also $62.50 in additional fees. Here are where they go:

- $1 for Peace officer Standards and Training Committee,

- $2 for Shelter for Battered Persons Fund,

- $2 for Spinal Cord Injury Fund, and

- $4 for Prosecuting Attorney’s and Circuit Attorney’s Retirement Fund.

There are a couple of worthy causes listed. But where I come from, charitable giving is strictly voluntary.

The Human Cost

In the spring of 2014 in the St. Louis North County town of Florissant, Nicole Bolden, 32-year-old single black mother of two, was driving her car with her kids, aged three and one-and-a-half. A car in front of her made an illegal U-turn, and Bolden couldn’t avoid a collision. The police were called.

The officer ran her name and discovered that Bolden had arrest warrants in four separate North County jurisdictions. All warrants had to do with traffic violations and the aforementioned failure to appear. According to a Washington Post article on this and other North County incidents, defense attorney call these offenses “poverty violations”…driving with a suspended license, expired plates and registration, no insurance, failure to appear in court. The article continues:

The Florissant officer first took Bolden to the jail in that town, where Bolden posted a couple of hundred dollars bond and was released around midnight. She was next taken to Hazelwood and held at the jail there until she could post a second bond. That was a couple of hundred dollars. She wasn’t released from her cell until around 5 pm the next day. Exhausted, stressed and still worried about what her kids had seen, she was finally taken to St. Charles County jail for the outstanding warrant in Foristell…

By the time Bolden got to St. Charles County, it had been well over 36 hours since the accident. “I hadn’t slept,” she says. “I was still in my same clothes. I was starting to lose my mind.” That’s when she says a police officer told her that if she couldn’t post bond, they’d keep her in jail until May. “I just freaked out,” she says. “I said, ‘What about my babies? Who’s going to take care of my babies?'” She says the officer just shrugged.

It is not my intention to paint policing and municipal authorities with an unsympathetic brush. There are always some bad apples, but presumably most are doing their jobs as commanded by an upper echelon whose piggy banks are alarmingly empty. Simply put, state and local governments are starving for revenue. The reasons are clear:

- In the US Congress, Republican-imposed austerity, infamously known as sequestration, has drained outlays that “trickle down” to all levels of government.

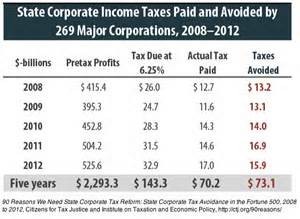

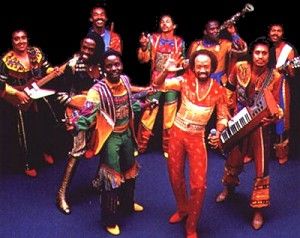

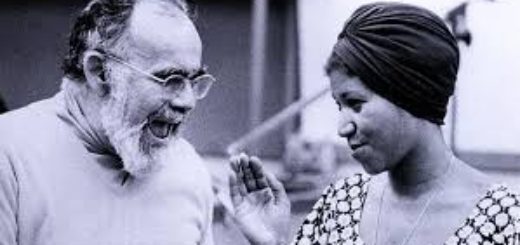

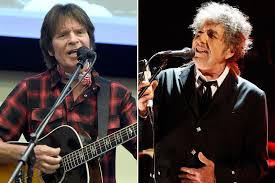

- A study by the Citizens for Tax Justice showed “that corporations pay less than half of their required state taxes…[and] the percentage of corporate profits paid as state income taxes has dropped from 7 percent in 1980 to about 3 percent today.” As indicated in the above graphic, 25 of our largest corporations ring up state tax payments of 2.4 percent, which is a third of what’s required by the tax code.

- This week, Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, Jr. reported on the regressive nature of state and local tax payments. A report by the Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) found that in 2015, “the poorest fifth of Americans will pay, on average, 10.9 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes and the middle fifth will pay 9.4 percent. But the top 1 percent will pay states and localities only 5.4 percent of their incomes in taxes.”

No More Policing for Profit

Back to St. Louis and its North County. In the aftermath of the shooting and the empanelment of the grand jury, local authorities became crusading reformers. The city of St. Louis began an amnesty program that allowed its citizens who failed to appear in municipal court to reschedule hearings without additional fines or imprisonment. Ferguson has halted issuing failure-to-appear warrants, and “is dismissing the charge in pending cases.”

These reforms are a good start, but they clarify that authorities have finally realized that wrong has been done. But here’s the thing: All half-measured remedies will fail until it is codified in law that no proceeds–fines, court costs, whatever–can be returned to benefit the authority that imposed them. It is wrong. It is unfair. It is corrupt.

Find another way. Or step aside, and let someone else figure it out.