The Blues Had a Baby and They Named It Rock ‘n’ Roll

Many Rock Songs Pay Homage to Elegantly Simple 12-Bar Blues.

‘Sweet Home Chicago’ Ground Zero for Great Blues Migration

For the record: A good percentage of rock and pop songs performed and recorded over the past several decades is musically based on a simple chord structure that has powered a particular type of African-American music we know as “the blues.”

Twelve-bar blues is one of the most ubiquitous chord progressions in popular music. It is based on the I, IV, and V chords of a key, 12 bars to a measure. It’s a simple, yet logical formula that found comfort among black musicians on plantations in the Deep South. Eventually, it worked its way north.

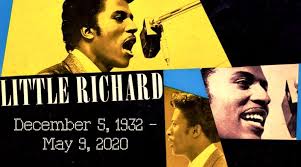

Examples of 12-bar infiltration into rock and pop music abound and delight. Bill Haley’s 1954 classic “Rock Around the Clock” is 12-bar blues. Little Richard’s “Tutti Fruitti” and ZZ Top’s “Tush” both qualify.

Led Zeppelin’s celebrated first album carried two blues standards, “You Shook Me” and “I Can’t Quit You, Babe.” Both were penned by the famed “songwriter of the blues,” Willie Dixon.

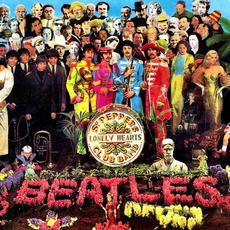

The most successful songwriting duo in rock history, John Lennon and Paul McCartney of The Beatles, found the 12-bar structure useful in songs such as “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Day Tripper” and “Birthday.”

In the early days of rock ‘n’ roll, many country-influenced musicians like Bill Haley stood out from the crowd by making the transition from “ballads to boogie.” Hip-swiveling Elvis Presley burst out of the Sun Studios in Memphis in 1955 with a song titled, “That’s All Right.” That song was written by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup who, 10 years prior, was the first blues performer to hit the Billboard R&B (then called “race”) charts.

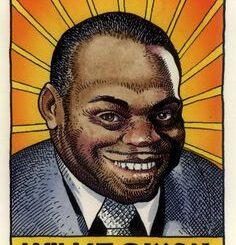

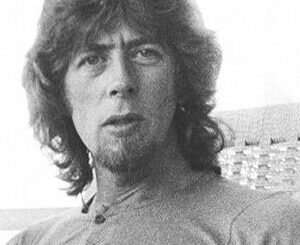

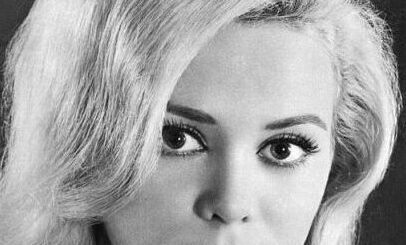

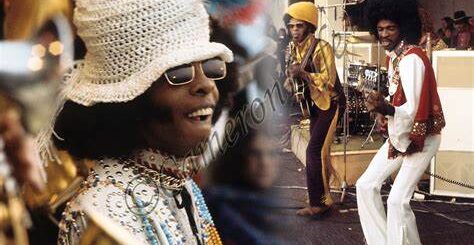

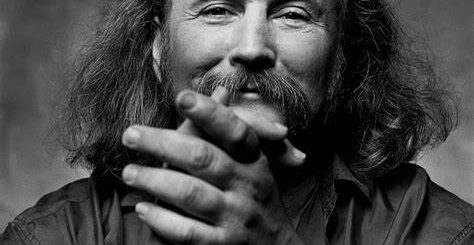

Muddy Waters

As a princely practitioner of Mississippi delta blues, McKinley Morganfield chose an appropriately “delta” stage name: Muddy Waters. In May 1943 Waters boarded an Illinois Central train destined for Chicago. Muddy Waters, well-known in the bars and juke joints along Highway 61 in Mississippi, was just another migrant black southern blues musician trying to gain a foothold in the big city.

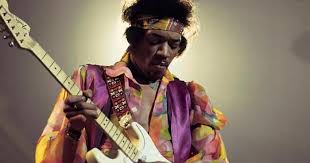

Eventually, Muddy wrote or made famous such songs as “Mannish Boy,” (Paul Butterfield, John Mayer) “I’m Ready,” (Aerosmith, George Thorogood) Rollin’ & Tumblin'” (Cream, Bob Dylan) and “(I’m Your) Hootchie Kootchie Man” (Jimi Hendrix, Allman Brothers) that endure as rock standards.

The great Robert Johnson helped teach guitar to Muddy Waters, but Johnson died too young to fulfill his Chicago yearning. Here’s one of his few recordings, published by shogun coredump via YouTube:

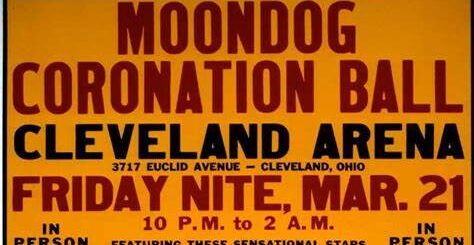

‘Sweet Home Chicago’ – The Great Migration

They say the Illinois Central Railroad brought the blues to Chicago. Between 1940 and 1950, Illinois Central trains bound for Chicago mainly originated in New Orleans. Travel time to Chicago varied, of course, depending on where you boarded. Trips took up to 24 hours. In 1940 fares were $16.95 from New Orleans, $15.35 from Jackson, MS, and $11.10 from Memphis. One way.

For many southern blacks, Chicago was already somewhat familiar due to a newspaper that was widely read in many black communities throughout the country. The Defender, Chicago’s black newspaper, was “actually exhorting Southern blacks to leave the farms and make Chicago their home.” It didn’t take much to convince a large number of poverty-stricken musicians to board that train. After all, Chicago was known as a “wide-open town.”

But who would listen to their music once they arrived?

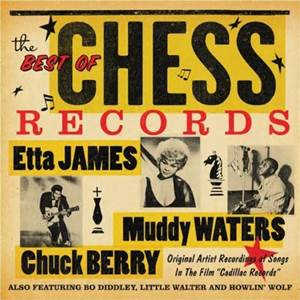

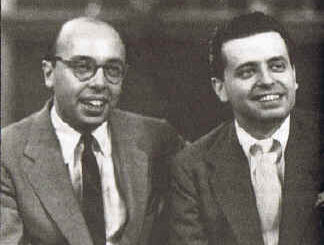

Chess Records

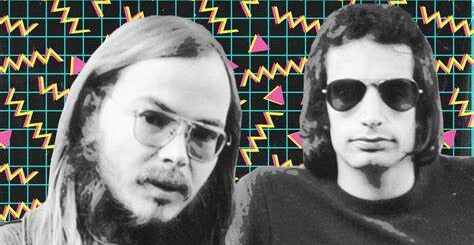

The brothers Chess, Leonard and Phillip, were Polish immigrants who arrived in the US on Columbus Day, 1928. They settled in Chicago and asserted their entrepreneurial talents in a variety of ways, including owning a few nightclubs. The brothers were stirred by the skill and popularity of their black nightclub performers…and astounded by the fact that no studio seemed to want to record their songs. Well, they would.

A performer named Lazy Bill remembers, “When I first saw Leonard Chess in 1946, he had a tape recorder no bigger than that, going around from tavern to tavern looking for talent.”

The Chess brothers bought a record company in 1947 called Aristocrat Records, and in 1950, hung their shingle. They moved into a shiny new recording studio on Chicago’s south side, immortalized by The Rolling Stones’ song, “2120 South Michigan Avenue.” (Leonard’s son, Marshall Chess, would manage the Stones when the group broke free of London Records and signed with Atlantic in 1971.)

Blues-Rock Triumvirate

Chess Records took its place in the rhythm and blues pantheon alongside Ahmet Ertegun’s Atlantic label and Sam Phillips and his Sun Records, home (for a while) to Elvis Presley. Atlantic Records recorded Ray Charles’s groundbreaking 1959 single, “What I Say,” with its sexually-charged call-and-response and its “bob shoe bop” choral background that would be imitated by The Beatles and white garage bands everywhere.

Blues Revival

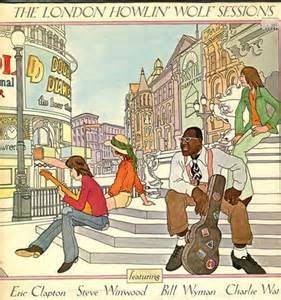

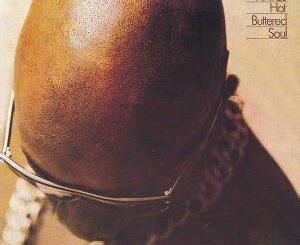

Fast forward to the year 1971. The blues revival in the sixties had not only upheld the notion that blues music was at the core of rock ‘n’ roll…but it also gave blues stalwarts like Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Little Walter, and especially Howlin’ Wolf a little bit of fame and fortune.

It’s hard for me to think of anything more well-deserved.