Civil Asset Forfeiture: Un-American Greed

Cops patrol vulnerable out-of-towners, looking for money and jewelry. How can this happen in America?

When I worked for a convention & visitors bureau in Ohio, there always seemed to be some noise about raising the “bed tax.” (A bed tax is an additional tariff imposed specifically on a visitor’s hotel tab.) My recollection, admittedly hazy, was that this bed tax, which was in addition to the sales tax, was ridiculously high…an eye-popping addition to the final bill.

When I asked my boss how the county could get away with this, he shrugged and said, “people who pay it come and go. They aren’t organized. We are.”

This reminiscence is important background as I ponder the topic of this post. A civil asset forfeiture occurs when some government jurisdiction imposes the confiscation of assets–physical property and cash–when criminal activity is evident or suspected. But according to the Economist, “unlike criminal forfeiture, in which prosecutors seize the proceeds of criminal activity as punishment for a crime, civil asset forfeiture does not require a conviction or even a criminal charge.” (emphasis mine.)

Though its origins were noble–the 1984 law imagined crippling an elusive drug lord by taking all of his bling–civil asset forfeiture (“forfeiture”) has become predatory, racist and anathema to anyone’s concept of fair play. It seeks out those least able to fight it. It embodies the pernicious elements of abuse of police power, criminalizing poverty and even reinstating debtor’s prison: all a pox on the house of American justice.

And yet…it survives. Forfeiture has no national constituency. It is not a left-right issue; both sides agree that it is grossly unfair. In fact, the conservative Cato Institute dedicates a portion of its website to denounce the “piratical state” and other libertarian rhetorical favorites. (Hey, I’ve gotten over it.)

Forfeiture is around because not enough people have called for its demise. Going back to the convention & visitors bureau analogy, it is simply a matter of: certain law enforcement interests are organized. People ensnared by forfeiture are on their own.

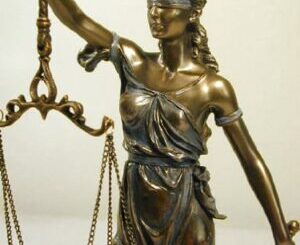

Remember the bizarre notion, uttered by a recent losing presidential candidate and endorsed by the Supreme Court, that corporations are people? Forfeiture splinters rationality along those lines, by positing that a piece of property, may it be a house, a car or a wad of cash, can be guilty of a crime. (As I will recount in more detail later, one of the first cases of forfeiture abuse in Tenaha, TX, was required to be filed as State of Texas vs. One Gold Crucifix.) If cops can remotely connect a piece of property to criminal activity, it is the property that matters the most.

In fact, 80 percent of people whose property was seized by the feds were never charged with a crime. How can this happen in America?

Getting your property back can be a time-consuming and expensive process. Very often, filing and attorney fees far exceed the value of the property seized. And in a further twist to judicial procedure, the burden of proof falls on the person whose valuables were seized.

In other words, “owners have to prove their innocence to get their property back, rather than the state having to prove their guilt.” In the freakish world of forfeiture, property can be guilty of a crime, but enjoys far fewer constitutional protections than…people.

I’m sure you can hear the drumbeat of countering arguments: the Great Recession and Congress-imposed austerity has stripped bare law enforcement budgets on state and local levels. Something has to be done to protect our children from those drug kingpins. Oh dear, oh my…

And yet: only a small portion of state and local forfeiture cases targets organized crime. According to Lee McGrath of the Institute of Justice, who studied Georgia’s forfeiture practices, 58 state, county and local police forces in Georgia collected $2.76 million in forfeitures in 2011. McGrath found that over half of the cash and property collected were valued at less than $650 per person. (emphasis mine.)

It is certainly true that law enforcement budgets are stretched. But there’s little to no oversight over the funds collected from forfeiture. In Hunt County, Texas, patrol cops were “scoring bonuses of up to $26,000 a year, straight from the forfeiture fund.” In Atlanta’s Fulton County, the district attorney’s office allegedly spent forfeiture funds on “a Christmas party, flowers, a security system for the district attorney’s home and assorted yummies including ‘mini-crab cake in a champagne sauce.'” County DA Paul Howard explained that such expenditures “have reduced turnover and improved morale.” You can find more examples of forfeiture proceeds abuse here.

Justice, Philly Style

In researching civil asset forfeiture, I owe much gratitude to author Sarah Stillman and her lengthy, groundbreaking article published by The New Yorker on August 12, 2013, titled “Taken,” which refers to “Americans who haven’t been charged with wrongdoing [who] can be stripped of their cash, cars and even homes.” Examples abound of forfeiture abuse. Here’s one:

The West Philadelphia rowhome of Leon and Mary Adams had served them well for over a half-century. It was just the two of them: Leon, a cook and handyman and Mary, a nurse at the Bryn Mawr Hospital. Well, make that three of them: Leon, Jr., 31, had left home, but returned to help out when his father suffered a stroke. The elder Adamses were blissfully unaware that Leon, Jr. had a little side business going.

That business was rudely revealed when cops busted Junior for selling $20 worth of marijuana to an undercover confidential informant. The transaction took place on the front porch of the Adams’ rowhome.

The next month, the couple awoke to a loud commotion. Heavily-armed SWAT-type officers raided the home…in fact, knocked down the front door with “some sort of big, long club” despite receiving no resistance from the elderly couple. The officers displayed an order to “enter, seize and seal” the premises; the Adams were given a 10-minute notice to pack their stuff and vacate.

Leon, Jr., was arrested and taken to jail. (Because of the elder Adams’ medical condition, the couple was allowed to stay for the duration of the forfeiture proceedings. The case is still pending.) Author Stillman:

The police returned a month after the raid. Owing to the allegations against Leon, Jr., the state was now seeking to take the Adams’ home and sell it at a biannual city auction, with the proceeds split between the district attorney’s office and the police department. All of this could occur even if Leon, Jr., was acquitted in criminal court. In fact, the process could be completed even before he stood trial.

Public records examined by The New Yorker support the assertion that Philadelphia homes are routinely seized for “unproved minor drug crimes, often involving children and grandchildren who don’t even own the home.” The forfeitures, the records showed, were overwhelmingly Hispanic and African-American. The Philadelphia DA’s office comment was, “It’s the law…we’re following the law.” It’s the old Nuremberg defense and it reeks.

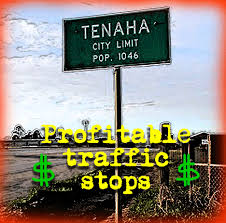

In the frightening saga that is civil asset forfeiture, Tenaha, TX, is where the proverbial rubber hits the road: US Highway 59, to be exact. Highway 59 connects Laredo, TX, on the US border with Mexico, to the urban center of Houston, TX. It was on that highway in Tenaha where Patrolman Barry Washington, acting in concert with county DA Lynda K. Russell, transformed forfeiture from a crime-fighting tool into a national disgrace.

Washington, a former state trooper, just showed up in Tenaha in 2006, and announced that his “drug-interdiction” skills would be very useful; specifically, “money from thugs could pay the town’s bills.” He was hired immediately.

Highway Robbery

You could hardly describe Jennifer Boatright as a “thug.” A waitress from Houston, Boatright was driving on Hwy. 59 with her two sons and her boyfriend, Ron Henderson, hoping to buy a car in Linden, TX. The sale would require cash, and so Boatright stashed her life savings in the car’s front console. She had just seen the sign welcoming her to Tenaha when she pulled into a roadside mini-mart. As she pull out of the parking lot, she noticed a patrol car shadowing her.

Patrolman Washington told Boatright the she was illegally driving in the left lane, a passing lane. He asked her whether she was carrying drugs; of course not, she replied. Washington claimed to have smelled marijuana (none was found), and proceeded to search the car. Boatright’s life savings were found, seized, and all four were transported to the Tenaha jail. Here’s what happened next, according to The New Yorker article:

The [Shelby]Â county’s district attorney…Lynda K. Russell, arrived an hour later. Russell, who moonlighted locally as a country singer, told Henderson and Boatright that they had two options. They could face felony charges for “money laundering” and “child endangerment,” in which case they would go to jail and their children would be handed over to foster care. Or they could sign over their cash to the city of Tenaha and get back on the road.

Boatright complied, but was naturally outraged. When the two complained to the county and asked for the return of her money, they received this in response: DA Russell warned them that “if they continued to contest it, they could be indicted on felony charges. ‘I will contact you and give you an opportunity to turn yourself in without an officer coming to the door,’ she wrote in a letter mentioning the prospect of a grand jury. Once again, their custody of the kids was threatened.”

Fighting Back

Boatright and Henderson decided to fight it anyway, and needed a lawyer. Several attorneys in the area told them to forget it; it was a lost cause. The were referred to a “small town civil rights lawyer” named David Guillory from nearby Nacogdoches, TX. The case cried out for a class action lawsuit, and attorney Guillory was already familiar with the “Tenaha operation.”

In fact, Guillory had just received a call from a one James Morrow, who was driving to Houston to get dental work done. Morrow was pulled over for “driving too close to the white line” and had his $900 cash, earmarked for his dentist, taken from him. “Morrow, who is black, was taken to jail where he pleaded with authorities to call his bank to see proof of a recent cash withdrawal. They declined.”

In seeking to attach other plaintiffs to the lawsuit, they found a treasure trove of victims who seemed to have these traits in common: Most were minorities, especially Latinos with a limited command of English; most were scraping to get by, and couldn’t afford to miss work; most had limited knowledge of, and access to, lawyers and the legal system; many, such as Boatright, had children to protect. In the annals of victimology, this was one for the ages…the dark ages.

Tenaha-ha-ha

In the fall of 2011, a Texas district court finally accepted–“certified”–all plaintiffs in the class action lawsuit. However, the district judge stipulated that the Tenaha victims could not expect to get all of their money back; that is, compensatory and punitive damages were out. “What we’ve asked the court to approve is a deal that requires the defendants to basically clean up their act,” explained Guillory.

The next year, the attorneys and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) agreed to a settlement of the lawsuit. According to the ACLU, officials of Tenaha and Shelby County agreed to policy changes requiring patrolmen to observe rigorous rules governing traffic stops:

All stops will now be videotaped, and the officer must state the reason for the stop and the basis for suspecting criminal activity. Motorist pulled over…can refuse a search. No property may be seized during a search unless the officer gives the driver a reason for why it should be taken. all property improperly taken must be returned within 30 business days. And any asset forfeiture revenue seized during a traffic stop must be donated to a non-profit organization or used for audio or video equipment…for training [police to be in compliance with racial profiling laws].

It was a huge win for the good guys. Victims are finally doing more than just shaking their heads, and saying, “This can’t happen in America.” It can and it does. There are many more Tenahas out there. Get the latest about forfeiture here and here. And leave your cash at home.