Innocence Project Trusts DNA Science to Free Over 300 Wrongfully Convicted

Mob-Cop Frame-up Netted NYC Man $9.9M

The noble work of the Innocence Project reentered my bandwidth recently with the premier of a cable TV scripted drama titled, “The Divide.” Set in Philadelphia, the show is about efforts to exonerate an innocent man who had already spent 11 years in prison based in part on the eyewitness memory of a 10-year-old kid.

The show’s characters are straight out of central casting: the crusading Innocence Project attorney (“Innocence Initiative” in the show), his persistent but flawed paralegal and the hard-nosed DA who occasionally reveals a conscience. The characters were accurate enough to remind me of the time I spent working for the Pennsylvania Innocence Project…an exhilarating stretch when I was counted on to evaluate claims of innocence.

The Innocence Project was founded in 1992 by Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld as a part of the Cardozo School of Law in New York City. Its entire mission is to exonerate people who are actually innocent by means of testing or retesting DNA evidence. A group profile of the wrongfully convicted: They’ve spent an average of 13 years in prison; 70 percent are a part of a minority group; only half of exonerees have been monetarily compensated for time lost in prison. Mistaken eyewitness identification is the leading cause of wrongful convictions. (More about this later.) To date, the Innocence Project has been involved in 317 exonerations due to DNA testing.

Think about it. Those are 317 precious lives interrupted and put through living hell for no valid reason…lives duly restored by science and this organization. Of course one is too many.

Nationally, around 3,000 prisoners write to the Innocence Project annually to request a review of their cases. All petitioners go through an extensive screening process to determine whether the Innocence Project will litigate their case. Of the active cases, “about 43% of clients were proven innocent, 42% were confirmed guilty, and evidence was inconclusive and not probative” in the rest.

Here is one success story. Damon Thibodeaux was convicted and sentenced to death in New Orleans, LA, for the 1997 murder of his half-cousin, 14-year-old Crystal Champagne. One of many initial suspects, Thibodeaux was interrogated for eight and a half hours (only 54 minutes were recorded) when he finally confessed to the crime. His confession contained details that were totally inconsistent with what actually occurred. Also, two eyewitnesses claimed they saw someone “pacing” near where the body was found. Both selected Thibodeaux from a photo line-up.

The Innocence Project took the case in 2007. DNA testing by a forensics expert concluded that, contrary to Thibodeaux’s “confession,” the victim was not sexually assaulted. DNA evidence from the crime scene (82 different specimens) ruled out Thibodeaux as the perpetrator, and pointed to an unknown male. Thibodeaux was finally exonerated on September 28, 2012, after spending 15 years on death row.

Mistaken Eyewitness ID

So what happened? It turned out that the eyewitnesses had already seen Thibodeaux’s face in the newspapers before taking part in the photo line-up. The fact is, mistaken eyewitness identifications are responsible for 72 percent of the 317 wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence.

To remedy this stain on our criminal justice system, the Innocence Project is advocating reforms to eyewitness ID procedures. To prevent line-up administrators from dropping unintentional clues, one reform would require the supervising cop to not know who the suspect is. Further, the eyewitness almost always assumes the perpetrator is included in the line-up. Instructions should emphasize that the suspect may or may not be present. It is quite logical that the eyewitness would become more diligent.

Coerced Confessions Hidden From Public Scrutiny

Damon Thibodeaux confessed to a crime he did not commit. But how could that be? Why would anybody put him or herself in such harm’s way? According to the Innocence Project, “In about 30 percent of DNA exonerations, innocent defendants made incriminating statements, delivered outright confessions or pled guilty.” False confessions are mainly the result of police interrogations in which the suspect is intimidated, threatened with force, deprived of his reasoning abilities due to stress, hunger and sleep deprivation, and subject to irrational fears based on untrue statements. It is glorified on television almost every night.

The obvious remedy: electronically record entire police interrogations, and make them a part of the public record. Let a jury decide whether the confession was coerced. To date, 15 states, the District of Columbia and 850 jurisdictions have reformed their interrogation procedures.

Compensating the Wrongfully Convicted

It is quite fair and reasonable that when an innocent man is deprived of his freedom, he should be compensated for the time he endured being locked-up through no fault of his own. When a man, wrongfully convicted or not, is released from prison, he very likely has no money, job, housing or health care. His relationship with his family is probably frayed. Thirty states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws to compensate the wrongfully convicted. Rates are often set by the number of years incarcerated, with a cap on total compensation. But the system doesn’t always work the way we would like.

Damon Thibodeaux is still waiting to be reimbursed for the 15 years he wasted on death row. Louisiana law allows awards of up to $250,000, for which Thibodeaux is easily eligible. But Louisiana’s attorney general sees a loophole instead of human suffering. Even though Thibodeaux’s case was tossed, an assistant AG declared, “We don’t know that he’s factually innocent…Somebody did it. But this is not a case where somebody’s been exonerated because we have DNA showing some else did it.” Huh? In other words, the state of Louisiana wants Damon Thibodeaux to find the actual killer in order to collect his money. The case continues.

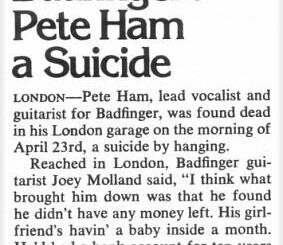

And then there’s Barry Gibbs. He was charged in the November 1986 murder of a black woman. The investigation was led by NYPD Detective Lou Eppolito, who is now doing life for betraying his badge and for being a hitman for demented Lucchese crime family underboss Anthony Casso. Gibbs was convicted and sentence to 20-years-to-life in prison based on eyewitness and “snitch” testimony…revealed to be orchestrated by Eppolito. Nine years after his conviction, Gibbs contacted the Innocence Project to inquire about DNA testing. And then, on March 10, 2005, according to the New York Daily News:

Gibbs was listening to the breaking news on the radio of Eppolito and partner Stephen Caracappa arrested by the Feds at their retirement homes in Las Vegas for selling out their badges to the mob. “I yelled out, ‘There is a God!'” Gibbs said.

Barry Gibbs was exonerated in 2005. In 2010 Gibbs settled a wrongful conviction lawsuit with New York State for $9,9 million.

Most of us feel rage when we view injustice. Many of us use that rage as a tool to urgently find a remedy. If that sounds good to you, I do recommend a book published in 2006 titled The Innocent Man. It is a non-fiction account of wrongful murder convictions of two Oklahoma men, Ron Williamson and Dennis Fritz, and how justice triumphed in the end. It was written by famed novelist John Grisham, who noted in the Author’s Notes afterword:

Wrongful convictions occur every month in every state of this country, and the reasons are all varied and all the same: bad police work, junk science, faulty eyewitness identification, bad defense lawyers, lazy prosecutors, arrogant prosecutors…Murder and rapes are still shocking events, and people want justice, and quickly. They, citizens and jurors, trust their authorities to behave properly. When they don’t, the result is Ron Williamson and Dennis Fritz.

John Grisham serves on the Innocence Project’s board of directors. He is an outspoken advocate of allowing scientists and not police to develop forensic techniques.