Vermont Heroically Battles Its Heroin Epidemic

But even with resolve and the tools to fight it, can it slay the monster?

In his 1988 book titled Hardball, on which his current television show on MSNBC is based, Chris Matthews laid down the rules of political engagement, “from one who knows how to play the game.” One of the rules enunciated by the long-time political operative was this: Hang a Lantern on Your Problem. According to Matthews, “Bad news has a habit of spreading. It is always better to create your own trial scene than to let someone else rig one up.”

On January 8, 2014 Governor Peter Shumlin, a Democrat from Vermont, devoted his entire annual state-of-the-state speech on the scourge of opiate addiction that’s afflicting a state otherwise knowing for its idyllic scenery, maple syrup and ice cream, its friendly and tolerant people and their industriousness.Of course Governor Shumlin was doing more than “hanging a lantern on his problem.” But his frank assessment of the problem and his decision to speak of nothing else last January thrusted Vermont into the forefront of a fractured national discussion about the prevalence of substance abuse among young and old…and remedies that still seem out of reach. He “did good.”

Supply and Demand

Gov. Shumlin’s speech summarized some of the numbers behind the crisis that were a bit reminiscent of the ongoing meth scourges in Appalachia and the Midwest. Here are the most heartbreaking:

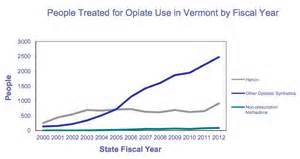

- Heroin addiction is up 770 percent in Vermont since 2000, with 4300 fresh cases of people being treated for opiate addiction in state treatment facilities in 2012 alone.

- Vermont spends $134 million a year to jail substance-addicted residents. Nearly 80 percent of inmates in the state are being held on drug-related charges.

- According to the Federal DEA, Vermont leads the nation in per-capita consumption of buprenorphine, a non-euphoric opiate compound used in the treatment of heroin addiction.

- More than $2 million worth of heroin and other opiates are illegally brought into the state on a weekly basis.

The governor’s remedies emphasized the enlightened approach of treating addiction not so much as criminal activity, but as a public health matter. According to the website The Fix:

While his approach seeks tougher laws on drug dealers, Gov. Sumlin outlined a plan that placed a heavy reliance on treatment, education and prevention. He pointed out that incarcerating addicts for a week costs the state $1,120 while a week of treatment at a state-financed center costs only $123. With over 500 addicts presently on waiting lists, Gov. Shumlin seeks a broad expansion of the availability of treatment programs.

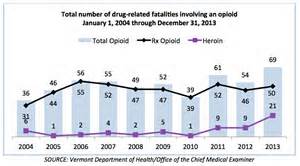

Hmmm…treatment programs. We’ll get back to that. But in the meantime, there’s good news: the state has been able to pass a 911 Good Samaritan Law, which grants immunity to participants who seek medical help after witnessing an overdose. The state has distributed 1,175 overdose rescue kits (with the opiate antagonist Narcan) to law enforcement officers, who have reportedly saved 67 lives thus far. Some 2,519 addicts are in treatment programs currently, up from 1,704, although there are probably long waiting lists.

Why Vermont, Why Now?

It seems that kids lately have increased their raids on their parents’ medicine cabinets to come up with all sorts of goodies. Perhaps they were unaware that one particular drug, OxyContin, was the most powerful opiate in pill form and highly addictive. But what happens when the cupboard is bare? According to the Burlington Free Press, “A single OxyContin 80-milligram dose purchased on the street costs $80 or more, and many opiate addicts say they need several ‘Oxys’ to get through the day. That can empty anyone’s cash reserves in quick fashion.” Strike one.

To combat reports of rampant addiction, the makers of OxyContin reformulated its product in 2010, making the pill turn to gel when crushed, and thus making Oxys impossible to snort or inject. Strike two.

Strike three: hello, heroin.

Invasion of the Dope Traffickers

In plain micro-economics, it is a no-brainer…for criminals, anyway. Buy 100 bags of heroin in New York for $6-$8 a piece, travel up to Vermont and sell each bag for $30. Wash, rinse, repeat. A central Vermont police officer, who asked to remain anonymous because he’s not allowed to speak to the press, said that he’s “seen dealers from New York City and Philadelphia creep into his jurisdiction. ‘They set up a distribution center in a cheap motel, and have the locals run for them,’ he said.”

Lt. Matthew Birmingham, of the Vermont State Police narcotics task force, added, “Addicts create this local network that’s established for any out-of-state source to come in and hook into any operation. From there they can distribute widely.”

In Vermont, like everywhere else, heroin doesn’t discriminate. It seeps into large and small towns alike. Not even the pastoral southern Vermont town of Bennington, population 17,000, known “for its pottery and classical music,” is immune.

“Anyone with open eyes can tell that there are listless groups of kids and young adults hanging out around town,” Bennington attorney Rob Woolmington told me. “Bennington has been the scene of some highly visible, possibly low impact drug enforcement raids. These involved helicopters flying low, swarming SWAT teams and doors theatrically broken. These do get people’s attention, but it is not clear that it’s having any lasting impact on the supply side.”

What especially got the attention of the good people of Bennington was a front-page article in the New York Times that examined the town’s growing drug plague. The article selectively focused on the miserable lives of a handful of townsfolk in the grip of addiction. The piece gave lip service to Bennington’s comparatively wholesome quality of life, but left the reader with the impression that “everybody does it.”

That didn’t sit well with Stuart Hurd, Bennington’s town manager. He fired off a letter to the Times to point out that the town has “made two successful drug sweeps and several arrests of major drug traffickers.” The town manager explained that state and locale had joined forces to “create a plan for enhanced substance abuse treatment in Bennington…which includes three important components of treatment: medical care, intensive psychological counseling and social services support.”

Obamacare to the Rescue?

At first glance, Vermont seems well-fortified to confront this pestilence. The state passed its own version of the Affordable Care Act (ACA or “Obamacare”) in 2011. Green Mountain Care was described as “a state-funded-and-managed insurance pool that would provide near universal coverage to residents.” If and when it takes effect, this will be huge in the fight against opiate addiction.

But implementation of Green Mountain Care could be delayed until the year 2017, as the state and federal government work out the details. The hitch: Vermont’s program is more substantive and inclusive, and would require an additional $2 billion to fund its “single payer” system. In the meantime, Vermont has launched a state exchange within the guidelines of the ACA.

The Affordable Care Act is helpful to Vermont’s predicament in two very important ways:

- It prohibits insurers from denying health coverage due to preexisting conditions…such as addiction and substance abuse.

- The ACA expands and codifies the so-called “parity rules,” which basically mean that insurance plans must cover mental health and substance abuse afflictions on the same level as physical medical care.

Both of these are transformative in the ongoing battle against drug addiction. According to one mental health official, “[Obamacare] enshrines in federal law that substance abuse is a medical issue–not one of poor morals, and not a criminal justice problem.”

The Devil Is In the Details

Yes, the devil is in the details. Let’s get back to treatment programs. It’s comforting for us (and reassuring to the loved one of suffering addicts) to think, let’s put the kids in treatment programs and everything’s going to be all right. Well, it’s just not that easy. Treatment comes in many forms. It ranges from “harm reduction” to drug therapies (some carrying lifetime addictions unless tapered willingly) such as buprenorphine and methadone to spiritually-based 12-step programs that encourage a lifetime membership in Narcotics Anonymous.

Concerning 12-step treatment, there’s a provision in the ACA that requires that addiction treatment be based on “evidence-based medicine. That means the treatment applied must be proven to work…in scientific studies. Unfortunately for 12-step methods of treatment, insurance will flat out refuse to pay because…it is not proven to be effective.” (emphasis mine)

This means that the vast majority of drug rehabs, all 12-step devotees, will have to radically alter their protocols to stay in business. To what? And how long will that take? This is what they call treatment, and it doesn’t come neatly packaged.

A Vermont Solution

Meanwhile, Vermont soldiers on, using whatever resources are available to it. The state is currently using what is called the “hub and spoke” model of treatment. Regional treatment centers are the hub, and a “network of primary care doctors, addiction specialists, psychologists and others [are] the spokes.” There is also a “rapid intervention” assessment for Vermonters arrested for possession of drugs, which could mean a diversion to treatment instead of criminal prosecution. There is joy among many addiction specialists that these ideas are finally seeing the light of day.

In Vermont, the joy is muted. A better day awaits. If there is one state that can pull together for the common good, its is Vermont. I wish it the best of luck.

Vermont is going to need some.